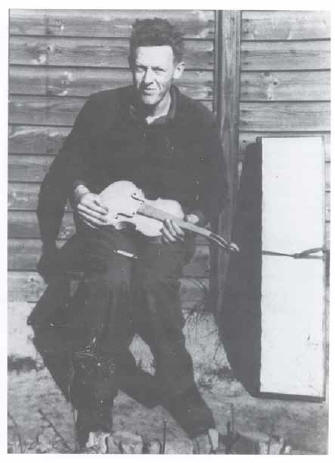

The Prison Camp Violin

Guidepost Magazine - January 1997

by Clair Cline, Tacoma, Washington

Stalag Luft I Prisoner of War

He carved it of rough-hewn bed slats with a penknife

traded for Red Cross rations. But would it play?

In February 1944 I was a U.S. Air Corps pilot

flying a B-24 bomber over Germany when antiaircraft fire hit our tail

section and we lost all controls. We bailed out and on landing I

found myself in a field in occupied Holland, just across the border from

Germany. We were surrounded by villagers asking for chocolate and

cigarettes. Then an elderly uniformed German with a pistol in an

unsteady hand marched me to an interrogation center. From there I and

other prisoners were shipped to Stalag Luft I, a prison camp for

captured Allied airmen.

The camp was a dismal place. We lived in rough

wooden barracks, sleeping on bunks with straw-filled burlap sacks on

wooden slats. Rations were meager; if it hadn't been for the Red

Cross care packages, we would have starved. But the worst affliction

was our uncertainty. Not knowing when the war would end or what

would happen (we had heard rumors of prisoners being killed) left us

with a constant gnawing worry. And since the Geneva Convention ruled

that officers were not allowed to be used for labor, we had little

to keep us occupied. What resulted was a wearying combination of

apprehension and boredom. Men coped in various ways: Some played

bridge all day, others dug escape tunnels (to no avail), some read

tattered paperbacks. I wrote letters to my wife and carved models of

B-24s.

The long dreary months dragged on. One day

early in the fall of 1944, I found myself unable to stand airplane

carving any longer. I tossed aside a half-finished model, looked out

a barracks window at a leaden sky and prayed in desperation,

"Oh, Lord, please help me find something constructive

to do."

There seemed to be no answer as I slumped amid

the dull slap of playing cards and the mutter of conversation. Then

someone started whistling "Red Wing" and my heart lifted.

Once again I was seven years old in rural Minnesota listening to a

fiddler sweep out the old melody. As a child I loved the violin and

when a grizzled uncle handed his to me I couldn't believe

it. "It's yours, Red," he said, smiling. "I never

could play the thing, but maybe you can make music with it."

There were no music teachers around our parts, but some of the

old-timers who played at local dances in homes and barns patiently

gave me tips. Soon I accompanied them while heavy-booted farmers and

their long-gowned wives whirled and stomped to schottisches and

polkas.

I thought how wonderful it would be to hold a

violin again. But finding one in this place would be impossible. Just

then I glanced at my cast-aside model, and a thought came to me: I

can make one! Why not? I had done a little woodworking before I was in the

service. But with what? And how? Where could I find the wood? The

tools? I shook my head. I was about to forget the whole preposterous

idea when something caught me. You can do it. The words hung

there, almost as if Someone had challenged me. I grew up on a farm

during the Depression, and had learned about resourcefulness. I remembered

my father doggedly repairing hopelessly broken farm

equipment. "You can make something out of nothing, Son," he

said, looking up from the frayed harness he was riveting. "All

you've got to do is find a way . . . and there always is one."

I looked around our barracks. The bunks. They

had slats! Each was about four inches wide, three-quarters of an inch

thick and 30 inches long. A few wouldn't be missed. Just maybe, I

thought, just maybe I could. I already had a penknife gained by

trading care-package tobacco rations with camp guards who delighted

in amerikanische Zigaretten. Glue? It was essential. But glue was

practically nonexistent in a war-ravaged country. "There's

always a way," echoed Dad's words.

One day I happened to feel small, hard droplets

around the rungs of my chair. Dried carpenter's glue! I carefully

scraped off the brown residue from a few chairs, ground it to powder,

mixed it with water and heated it on a stove. It would work. I

cut the beech bed slats to the length of a violin body and glued them

together. Then I began shaping the back panel. A sharp piece of broken

glass came in handy for carving. Other men watched with interest, and

some helped scrape glue from chairs for me.

Weeks went by in a flash. I shaped the curved

sides of the body by bending water-soaked thin wood and heating it

over the stove. My humdrum existence became exciting. I woke up every

morning and could hardly wait to get back to work. When I needed

tools, I improvised, even grinding an old kitchen knife on a rock to

form a chisel. Slowly the instrument took shape. I glued several bed

slats together to form the instrument's neck.

In three months the body was finished,

including the delicate f-shaped holes on the violin's front. After

carefully sanding the wood, I varnished the instrument (that cost me

more cigarettes) and polished it with pumice and paraffin oil until

it shone with a golden glow.

A guard came up with some catgut for the

strings, and one day I was astonished to be handed a real violin bow.

American cigarettes were valuable currency, and I was glad I hadn't

smoked mine.

Finally there came the day I lifted the

finished instrument to my chin. Would it really play? Or would it be

a croaking catastrophe? I drew the bow across the strings and my

heart leaped as a pure resonant sound echoed through the air.

My fellow prisoners banished me to the latrine

until I had regained my old skills. But from then on they clapped,

sang, and even danced as I played "Red Wing," "Home on

the Range" and "Red River Valley."

My most memorable moment was Christmas Eve. As

my buddies brooded about home and families, I began playing

"Silent Night." As the notes drifted through the barracks a

voice chimed in, then others. Amid the harmony I heard a different

language. "Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht, alles schläft, Einsam

wacht . . . " An elderly white-haired guard stood in the

shadows, his eyes wet with tears.

The following May we were liberated by U.S.

troops. Through the years, the violin hung proudly in a display

cabinet at home. As my four children and six grandchildren grew, it

became an object lesson for escaping the narcosis of boredom.

"Find something you love to do," I

urged, "and you'll find your work a gift from God." I'm

happy to say all of them did. In the fall of 1995 I was invited to

contribute the violin to the World War II museum aboard the aircraft

carrier Intrepid in New York. I sent it hoping it would become an

object lesson for others. But I was not prepared for the surprise

that followed. I was told the concertmaster of the New

York Philharmonic would play it at the museum's opening. Afterward he

called me. "I expected a jalopy of a violin," said maestro

Dicterow, "and instead it was something looking very good and

sounding quite wonderful. It was an amazing achievement."

Not really, I thought. More like a gift from

God.

Since CLAIR CLINE returned from World War II, The

Prison Camp Violin he made has been heard in concert halls across the

United States. Most recently it was played by Glenn Dicterow of the

New York Philharmonic during a ceremony at the Intrepid

Sea-Air-Space Museum in New York City. "Violins have to be used

if they are going to remain effective," says Clair. "I

believe I need to stay active too." Now that he has retired

from cabinetmaking and construction work, Clair and his wife, Anne,

stay busy growing fruit, flowers and vegetables in their garden. The

couple recently celebrated their 57th wedding anniversary, and their

four children and six grandchildren are the joy of their lives. Music

has remained important, and oldest son Roger, granddaughter Jennifer,

and grandson Daniel, play in the Chicago, National, and Arkansas

symphony orchestras, respectively.

As their children grew up, the violin rested in a display case in the

Clines’ home. Each child was told the violin’s story as a lesson in

resourcefulness. But its value goes far beyond that.

|