|

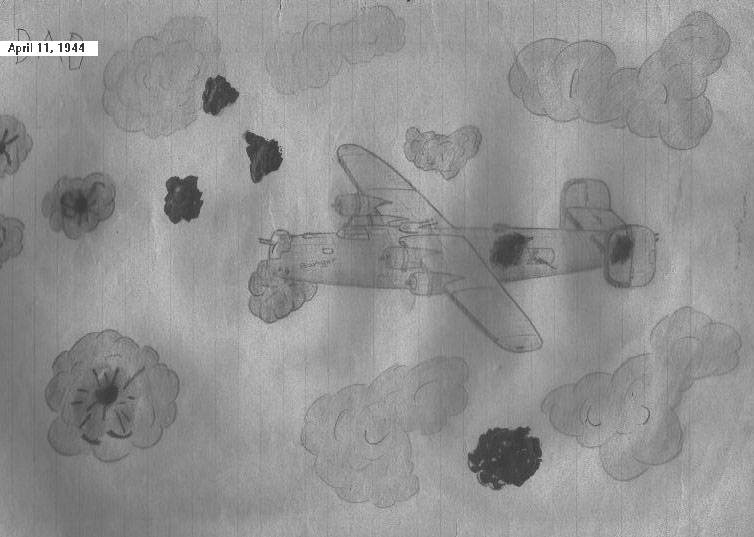

April 11, 1944. On this day, the lives of ten men changed drastically.

We were scheduled for a bombing mission deep in the enemy briefing was

in the early morning and there were the usual groans when the target was

revealed. We were a seasoned crew and had gotten over the adrenaline

shock but you could see the concern on the faces of the newer crews. Our

regular plane the Banger was in the shop for maintenance and we were

scheduled to fly #572 which belonged to Lt. Wylie.

And of course he was there to remind us that it was

his airplane and it was fairly new and we were to bring it back in one

piece. Yes, he was serious. #572 had two names. On one side it was the

Werewolf and on the other it was Princess O'Rourke. Take off was normal.

The climb to altitude, the gathering of the formation, the flight over

the channel, and the approach to enemy territory was uneventful.

On the way to our target, we were required to cross

the Dummer lake area. We had been there before and knew what to expect.

The flak in that area could be moderate or heavy. One of our planes

flying the low left position dropped out of formation and turned back

toward England. I flew into his position and shortly thereafter, we

encountered more flak bursts. When a flak shell bursts, there is a

bright red flash which disappears almost immediately to be replaced by a

starkly black cloud. You very seldom see the red flash but you can see

quite a bit of the black cloud. It is frightening because you know that

the probability of damage is at that very moment. Those black clouds

enlarge and take on an ominous shade of grey.

The first indication that we were hit was a violent

jarring of the airplane. A shell had burst directly below our number two

engine. When flak bursts, shrapnel is blown upward. The worst place to

be is directly above the bursting flak. Our engine was knocked out of

commission and was burning fiercely.. Our first action was to hit the

feathering button. Lt. Poore, the copilot, turned off the fuel to that

engine. The propeller failed to feather. Sgt. Korte, the engineer,

appeared quickly and tried to assist in putting out the fire.. We were

having no luck and knowing that a fire of that type could easily spread

to the wing fuel tanks, I pulled slightly off the left of the main

formation so that if my plane exploded, the other planes in the

formation would not be affected.

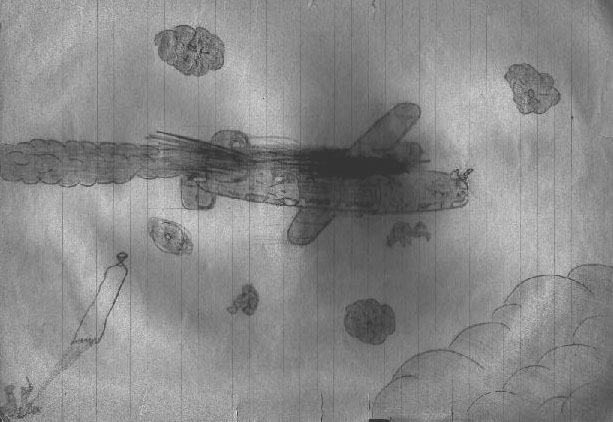

What I didn't know at that time was that we had a

hole in the waist of the plane that was large enough to jump out of and

the entire fabric cover on the inside of the left vertical stabilizer

was blown away. My engineer informed me that the engine was starting to

melt off. I turned and saw the cowl flaps melting away. It was only a

matter of seconds before the flames reached the fuel tanks. For some

reason or other, I accepted the fact that we were going to die and only

a miracle would save us.. I believe that at that moment, shock began to

set in and I became very mechanical. I pulled the plane away from the

formation and turned back toward England. I gave the order to bail out.

I saw the bombardier's head appear in the glass hatch directly in front

of me. Lt. Day's face was one big question mark. He had been so busy in

the nose turret watching for enemy aircraft that he did not know the

seriousness of the situation. However, he did notice that the navigator

was gone. I gave him a nod and a hand signal.. I then had to keep the

plane level so that my copilot and Lt. Day could safely leave the

aircraft. When I saw that the copilot was gone from the flight deck, I

moved from my seat and retrieved my chest chute from behind my seat.

Everything I did was very methodical.

Drawn by me while in prison camp

on lined tablet furnished by Red Cross.

I knew I was not going to make it and

there was no reason to hurry. I got to the edge of the flight deck only

to find that my copilot was lying on the cat walk staring up at me. He

had picked up his chute by the rip cord and had tried to get out with

the spilled chute in his arms. However, he could not go out because the

spilled chute was trailed up on the flight deck where I was. Had he

rolled out, he would have been killed. I turned and gathered up his

chute and carried it to the edge of the flight deck and dropped it to

him. My heart went with him as he rolled off the cat walk into the slip

stream.. It's bad enough to bail out of an airplane but when your only

means of survival is gathered loosely in you arms, it can be horribly

frightening. One panel of his chute was ripped open as he slid past the

ball turret guns. He received a bad gash on his knee but he made it

safely to the ground three miles below. I don't think Lt. Poore ever

recovered from that traumatic experience. When the war ended, he

returned to civilian life and did not fare well. He died before reaching

60.

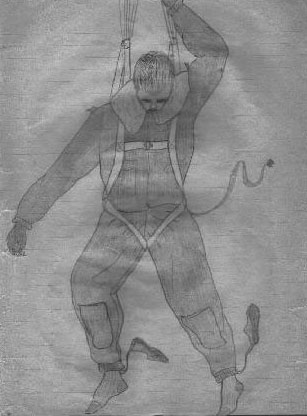

I crawled down to the catwalk and rolled out.

Suddenly I realized that I was not going to die. My body was turning and

flipping rapidly. Remembering the little training that we had received,

I went into a spread eagle position. Immediately, I straightened out,

flat on my back with my arms and legs slightly bent upwards. I had lost

my flying boots and I saw that my heated slippers had come off but were

still attached to the cord which ran down the legs of my trousers. There

were those two slippers about six inches above my feet. They appeared to

be frozen because there was no whipping in the wind. The heated cord

which came from my waist also was standing straight up. I worried about

that cord because I was afraid that it might tangle in the chute when I

opened it. When I reached up to pull in the cord, I changed my spread

eagle position enough to start rolling.

That was an uncomfortable feeling but I felt the need

to store that cord was more important so I reeled in all three feet of

it and stuffed it into my trousers. My oxygen mask was still attached to

my head. I do not remember detaching the oxygen hose from the aircraft

when I left the pilot's seat. And of course the hose was standing

straight up from my face. The wind going by the hose caused a venturi

effect and created a slight vacuum making is hard for me to breathe. I

yanked the mask from my head and threw it away. Much to my surprise, it

dropped up. It was then that I saw a very large explosion well above me.

It was not flak so I assumed it was an airplane and probably ours. I

dropped about 15,000 feet and when I could see the windows in a farm

house, I opened my chute. Another surprise occurred. The sudden

deceleration gave the sensation of going back up and after falling all

that way, I certainly did not want to go back up again.

While floating to the ground, I saw a fighter

aircraft which appeared to be a P-47 flying at low altitude. I didn't

float very long before hitting the ground. My landing was very hard. I

came in at an angle toward what looked like a barbed wire fence. In

order to miss that fence, I slipped some air from the chute and landed

directly against the side of a ditch. My knees and arms took most of the

impact. I wasn't knocked out and fortunately had no broken bones. An

older man and a young boy were standing very near where I landed. I

asked if they were Dutch. The old man replied "Ja, Deutsche". Not being

versed in the language, I believed that we might have gotten back to

Holland. I insisted that we were friends to no avail. I later learned

that Deutsche means German. Since I was having no luck with them, I

decided to get away from there as quickly as possible. The nearest trees

were about 100 yards away. Then I noticed a German soldier walking

toward me. He was too far away for me to see if he had any sharpshooter

medals pinned on him but since he did have a rifle, I thought it best to

stay put.

I was taken to a small village where I was united

with my copilot, navigator, bombardier, and two of my enlisted crew

members.

NOTE

I just learned in 1998 that

records show that #572 crashed on a road to Wagenfeld near Ströhen west

of Diepholz. This will give me a lead in finding the village where we

were captured. I plan to go there some day.

We were not put into a jail but were kept in the

village square under guard. The townsfolk were very curious and it

seemed that they had never seen American flyers before. They did not

appear to be openly hostile. Irv.., our bombardier, had some sulfa

powder which he applied to the copilot's injured knee. Eventually we saw

and heard the bombers on their return home. There was no attempt by the

villagers to take cover. Although they knew they were not the target,

there was a siren alarm which sounded the all clear.

It was now late afternoon. A large panel truck

arrived and we were loaded into the rear where we noticed several canvas

stretchers and shovels, all of which were stained with dried blood. It

entered my mind that we were going to be forced to dig our own graves. I

am sure that the rest of the crew were not very optimistic about what

was going to happen. We were taken to a field where a B-24 had crashed.

We had about 5 German soldiers guarding us. One of them made me think of

Napoleon. He was dressed in a very impressive uniform. Later in prison

camp, I drew a picture of him from memory and still have it. We were

required to gather up what was left of the bodies and carry them to a

corner of the field where we covered them with the remains of a burnt

parachute.

We were then driven through the farmland and stopped

in front of a farmhouse where we were joined by an American officer who

was determined to tell us nothing more than his name, rank and serial

number. After we informed him of what we had been forced to do, he

volunteered that he was a crew member on a B-24 that had crashed nearby

and while in the farmhouse he had heard bombs exploding. He was the

bombardier on that plane and knew that there were delayed fuses on those

bombs. Even the Germans were not anxious to go near the crash site.

Finally, the Napoleon decided that the bombs had all exploded and we

could get on with the clean up. Upon arrival at the crash site, it was

obvious that some of the bodies had been blown apart and others had been

burned. It was not a pleasant smell nor was it a pleasant sight.

Being the officer in charge, I decided it was time to

invoke the provisions of the Geneva Convention. Surprisingly enough,

Napoleon understood the words "Geneva Convention" because he repeated

them and laughed. He kept shouting a word "arbutin". I threw my shovel

to the ground and said "No". He undid the flap on the gun holster and

glared at me. I said "No" again. He removed the gun from the holster,

cocked it, and pointed it at me. I wisely picked up the shovel, turned

to the crew members, and told them to stay there while I went into the

wreckage and looked over the situation. I then turned to Napoleon and

requested that one of his guards go with me. He understood what I wanted

and turned to one of the guards and gave him instructions. The guard did

not like that at all. I walked into the center of the wreckage and was

unable to determine whether or not all the bombs had exploded. From what

the bombardier had told us, it had been well over two hours since the

last bomb had exploded. I figured the sooner we got the job done, the

better our chances of getting away from the possible danger. The crew

started to work but as time went by, more and more of them got actively

sick. Eventually I was alone in the center of the wreckage with my

guard.

The bomber had gone in at 30 degree angle. The pilot

and copilot were in their seats and the engineer was standing directly

behind them. It appeared that they might have been trying to pull out of

a dive. All three were badly burnt. As I tried to remove the body of one

of the men, I found that I could not extract his arm. It was entangled

in some metal, and without getting that person out, there was no way to

get the others out. It became apparent to me and the guard at the same

moment that the arm would have to be severed. He gave me a look that

said "You wouldn't dare". I raised the shovel high in the air and jabbed

it sharply into the arm just below the shoulder. My guard then joined

the actively sick. I followed him out of the field and Napoleon decided

there was no use in continuing. I don't know why I did not get sick. It

might have been that I had already seen a sight similar to this. (In

about 1936, an interurban train had crashed into a freight train in

Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. Some 50 people were killed in the resulting fire.

The scene and smell were very similar. I was 15 then and was very upset

viewing that wreckage.)

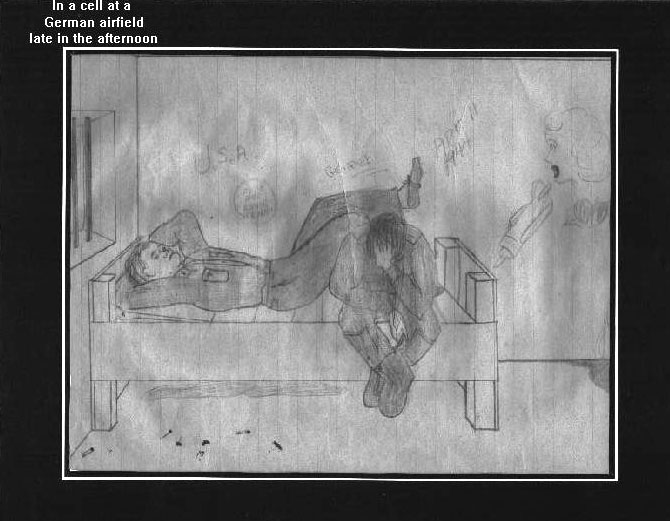

We were then taken to an airfield where we were put

into cells very much like a small jail facility. About ten o'clock in

the evening, we were allowed into the center hall where the Germans had

placed a table with dark bread and a jam made with beet sugar. I think I

was the only one who ate an appreciable amount. Most of the crew ate

nothing. I really think I was in a state of shock that continued well

into the first month of prison camp.

The next morning we were joined by an American Air

Force pilot. He had been shot down while on a low level strafing

mission. He was captured by civilians who were very angry and accused

him of killing a small child. He was very frightened because they had

threatened to kill him. He was actually rescued by soldiers who

eventually brought him to join us. I later tried to compare his

frightening experience with my own. He was white and shaking and I had

gone into shock. The circumstances where not quite the same.

We were put on a train and taken to a small town

where we were allowed to leave the train and stand on the passenger

loading platform. I heard someone shout "Hey Tuck". About 40 yards away

was another large group of prisoners. I saw my other four crew members

waving at me. I knew then that we were all alive. We reboarded the train

and eventually arrived a Frankfurt where the interrogation center was

located. We were herded into an open area in front of a barracks. Every

few minutes, a German soldier would appear at the door and call out a

name. That name was usually that of an American pilot. Very shortly

after the pilot entered the barracks, the German would reappear and call

the names of the crew members of that pilot. It appeared that they were

using a very effective method of gaining that information. I whispered

to my copilot that I would not give them any information other than my

name, rank, and serial number. Soon my name was called and I entered the

barracks. I was taken to a cell and locked in. There was no

interrogation on that day. Later my crew informed me that shortly after

I entered the barracks, the names of all my crew members were called.

There did not seem to be any way that the Germans could know that we

were a crew. My crew wondered how the Germans had gotten me to talk so

quickly. As it was I was not even asked who I was.

Late that afternoon, I heard some German commands

outside my small window. I looked out to see a squad of German soldiers

with rifles, leading a blindfolded American prisoner to the far end of

the building where they disappeared behind a row of bushes. There was a

volley of shots. The Germans reappeared this time carrying a stretcher

on which there was a covered body. Later I learned that I had witnessed

a little show that was seen by many other prisoners at Dulag Luft. I

doubt if anyone had ever been shot there.

On the morning of the 15th of April, I was

interrogated. A young German officer who spoke very good English, asked

me several questions to which I answered by saying that I could not give

him any information other than my name, rank, and serial number. Midway

during the interrogation, he pulled out a book that looked very much

like a large picture album. In that book was an aerial picture of our

airbase. Sections were numbered and by the legend one could determine

what was at each location. They knew right where the bomb dump was. I

was surprised at how much information they had on me. They knew where I

had gone to high school. They knew the number of my airplane that I flew

regularly. They knew where I had trained in the United States. There

were several pictures in the book. One was a picture of my commander but

the caption said he was a Major. The German officer said "You might

notice that he has been promoted". I had the impression that there was

nothing I could tell them that they did not already know. But I also

knew that they were trying to give that impression. It was a very

pleasant interrogation and I was not required to give anything more than

the name, rank, and serial number.

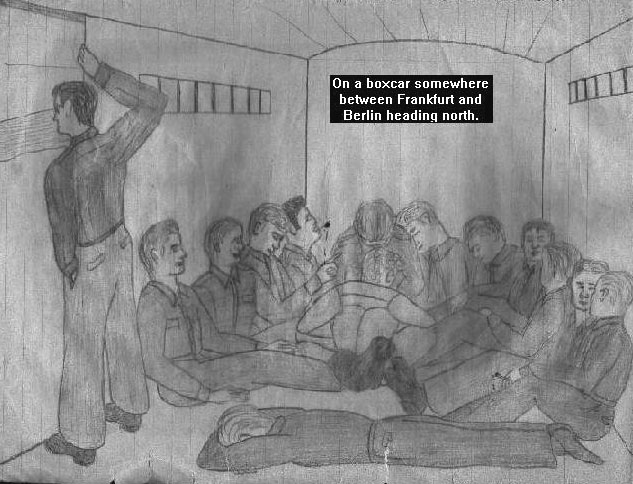

The officers and the enlisted men were then separated

and sent to the various prison camps. My crewmen went to the famous

Stalag Luft 17B. The officers in my shipment went to Barth, Germany

where Stalag Luft 1 was located. We traveled north in a boxcar. Four

German guards had one end of the boxcar and about 40 of us were in the

other end.

Another of my drawings.

There was straw on the floor and no facilities. We

traveled both day and night. We arrived at Berlin one night and were

taken below ground during an air raid. We must have gone 5 floors below

ground to a room where there was a pot bellied stove. We huddled around

that stove turning so that our front sides and back sides were warmed.

You can imagine forty men trying to stay warm around one stove. No one

slept that night. The next morning we were put back on the train which

continued north. In order to sleep, we had to lie like sardines. If one

man turned, all the rest of us turned. I was still wearing my flight

slippers but some of the prisoners had shoes. One very tall American had

shoes and very big feet. After being pummeled several times by those big

shoes, I decided to give him a hint that I did not like it. I kicked him

in the shins and woke him from a sound sleep. He sat up and tried to

determine who had done it. But of course we were all asleep. It seemed

to make a difference because he was more careful about where he put his

feet. In order to relieve ourselves, we went to the door of the boxcar

and performed.

On April 20th, we arrived at Barth only to find that

the houses were decorated and the townspeople were out to meet us. It

struck me as odd that they would greet us by decorating the houses but

when they started to throw rotten tomatoes and eggs at us, we knew that

we were not the cause of the celebration. April 20th happened to be

Hitler's birthday.

At the camp, we were taken into a holding area where we were divested of

our clothes and run through a debugging process. From there we territory

of Germany This was to be our next to last mission. One more after this

and we were going home. Not much was different. The were taken to an

entrance area where we were greeted by the prisoners who now lived in

the camp. They hollered at us and asked what the latest news was.

Several of them recognized friends among our group. Suddenly a fight

broke out among the group inside the fence. Two guys were really going

at each other. Then we realized that it was all put on. Those two

comedians put on many a show for the entire camp. Our fenced area was

called North Compound 1. The south compound was primarily British some

of whom had been there two or more years. My copilot who had the damaged

knee was put in the South compound. My bombardier, navigator, and I were

assigned to North 1. I went to a 16 man room in barracks nine. One of

the first things I did was to take a shower. Nine days without a bath or

a shower is just a little too long. I started my 13 month stay as a

clean prisoner.

Almost every room in the compound had a map on one

wall. In the first months we received air raid information and

shipping reports. Then after D Day, we received data on the location of

the front lines. As the allies would move across France and Germany, we

would color map with a different color for each month. The German guards

who entered the rooms during roll call or for some other reason, would

study the maps and wonder how we got the information. They never did

locate our radio. Course, there never was a radio. We got the

information from a cooperating German Major.

I was assigned to a 16 man room in barracks #3. I may

be wrong about the number of the barracks but on the drawn map, it is

located in the proper position. Here are the names of the 15

men in my room.

|

North 1 - Barrack 3 Room

"Unknown" |

|

Robert F. Bogner |

Chicago, Illinois |

|

Jack R. Bonham |

Bluefield, West Virginia |

|

Malcolm E. Daniels |

Fresno, California |

|

James W. Davies |

West Pittston, Pennsylvania |

|

Toivo E. Eloranta |

Bozeman, Montana |

|

Tom L. Gardner |

California |

|

Van Hixson |

Salt Lake City, Utah |

|

Jim W.

Hutchison |

Mt. Vernon, Washington |

|

Joseph

F. Krejci |

Cleveland, Ohio |

|

Peter V. Lovero |

Santa Ana, California |

|

H. F. Morrison |

Rosemead, California |

|

Ralph H. Stowe |

Portsmouth, Virginia |

|

George E. Syme |

Colorado Springs, Colorado |

|

Sterling L. Tuck

see also barrack 1 |

Akron, Ohio |

|

Henry J. Varela |

Salt Lake City, Utah |

|

Robert C.

Westmeyer see also Barrack 2 Room 14 |

Los Angeles, California |

If you have seen the movie "Stalag 17", you know what

the rooms looked like. The movie set was very realistic as far as

portraying the looks of the barracks and the rooms. We had wooden double

bunks. There were no springs and the mattresses and pillows were burlap

filled with hay. The hay would mat very quickly causing us to fluff the

hay about every other day. We had a small charcoal stove. It would amaze

you to see what some of the Kriegies had done to the stoves. Some had

blowers to help in starting the fires. Of course these blowers were

usually used in escape plans but we couldn't let the Germans know that.

The term "kriegies" is short for Kriegsgefangener

which is (I think) the German word meaning "captured at war". Prisoner

of war is more like Haftling kriege. As you can see my German is very

limited. On a recent trip to Germany, we found that we very seldom had

to speak German. We stopped at a little restaurant-bar in Prum and our

waitress did not understand English so I tried to order in German. I

said that I would like a beer and my wife would like white wine with ice

on the side. The waitress walked away and said something laughingly to

the bartender as she passed. I then realized that "ice" can be

interpreted as "eggs". I called her back and after going through several

explanations, I got her to understand that ice was sehr kaltes wasser,

(very cold water with knocking on the table). Ah ha, she understood ice

cream. We got the ice and our meal was delightful.

A little about the guys in my room. Eloranta was a tall blond Swede who

was a whiz at bridge playing and not too bad as a first baseman on our

softball team. Krejci was from Cleveland if I remember correctly.

Morrison worked in a lumberyard and had a mathematical mind. One day I

was working on a math problem. Someone asked what I was doing and I

replied "I'm trying to find the fourth root of 456,976". Morrison was

lying on his bunk reading a book. He put the book down and after about 5

seconds said "Twenty-six". I was shocked because I had never considered

Morrison to be on the intellectual side. About that, I never did change

my mind but one thing was for sure. He had a mathematical mind. Tom

Gardner. I don't know what Tom did before entering the service but I

classified him as a used car salesman. He was a sharp trader. He knew I

did not smoke and had saved several packs of cigarettes. He suggested we

set up a dice table outside our barracks. Of course, I put up the money

(cigarettes) while he made the table in real Las Vegas style. We did

very well for about three days except that cigarettes were getting a

little shabby. Some were reduced to tobacco. Eventually, a lucky shooter

came along and we were cleaned out.

Ralph Stowe was the only person in our room who was

successful in escaping from the camp. He was eventually captured and

returned. The wheels who were in charge of escape plans, tried their

best to find our how he did it and he would not tell them anything. I

have a good idea because he discussed his plan with me. He and I were to

make German work uniforms from the bed sheets. He made a jacket and I

made a pair of trousers. I had no intention of escaping with him because

his plan was to watch the guards in the towers and when they were both

looking in the opposite direction, we were to run to the barbed wire

fence, crawl up, jump over, and casually walk down the road. Physically

it would take a very good jump because the barbed wires were in two rows

spaced about 6 feet apart. The advantage was that the posts had been

staggered and the opposing fence sagged slightly. We spent several days

watching the guards and timing the opportunities. There were many times

that they looked away from our position for as much as 2 minutes. That

would have been plenty of time to get over the fence. As I saw it, it

was a big risk because there was no assurance that the guards would turn

around. And the fact that we knew the guards would shoot, made it less

desirable. One day at roll call, it was obvious that someone was

missing. Yep, it was Stowe. I looked under my mattress and sure enough,

my trousers were gone. I was not upset and wished Ralph the best of

luck. He was captured because it was cold and the potatoes were frozen

under the ground and dogs love to bark at strangers.

Stowe is the only person in that room that I have

talked to since leaving the camp. A few years ago, I talked to him over

the phone and he still would not tell me how he had escaped. He seemed

reluctant to talk to me and I have a feeling that he did not remember

who I was. It wasn't the kind of reunion that I expected.

George Syme. Nice quiet guy who pitched for our

softball team. He didn't have that big round up pitch which is so

prevalent among softball pitchers but he did have a big arc and could

really zing the ball across the plate. Jim Hutchinson. He was my

favorite. Red head from the State of Washington and had attended either

Washington U or Washington State. He played shortstop and was one of our

best hitters. I played third. We didn't do too well in the league.

Finished somewhere in the middle of the final standings. But we did

enjoy playing.

While I am into sports, let me tell about boxing. I was talking about

boxing one day and I guess the guys considered I was a blow hard. So I

asked if anyone wanted to put the gloves on with me. No one wanted to

but they managed to talk Hutchison into it. I don't think Red wanted to

box but he was sort of pushed into it. Well, Red was no boxer, and the

match did not last very long. On one of the holiday gatherings, Colonel

Zempke, the fighter ace, challenged anyone in the camp to a boxing

match. I believe it was to be staged on July 4th. Naturally the guys in

my room wanted to see their blowhard get his head knocked off. They

insisted so strongly, that I agreed to challenge Zempke. When I went to

the wheel barracks, there was a long line. Must have been 30 guys there

to challenge. I decided not to stand in the line but I must admit that I

was curious to know just how good he was. He finally accepted the

challenge of a paratrooper. The bad thing was that the paratrooper had

been wounded and I don't think he was back in good shape. They had the

boxing match and I was sorry I wasn't up there in the ring.

My big mouth got me into another match. A couple

thousand enlisted men had been brought in from Latvia or Lithuania. They

were housed in an area behind our mess hall. One of those young men was

from Akron, Ohio and looked me up to talk about home. We struck up a

casual friendship and during the course of the conversation, I mentioned

that I boxed. Not professionally but kind of neighborhood stuff. The kid

took the story back to his barracks and wouldn't you know but I was

challenged to a boxing match. I accepted and when I arrived in the

enlisted area, I found that they had set up a ring, appointed a second

for me and had a huge crowd of heavy bettors and were anxious to see

that "officer" get his nose broke. Someone mentioned that my opponent

was a former Golden Glove fighter from Chicago. We fought three two

minute rounds. It was a very good fight and I ate lots of leather.

Neither of us was bloody but both were tired and sore. Since the judges

were all enlisted, I figured I did not have much chance of winning. I

was truly surprised when they called it a draw. I had a feeling there

was much respect in that crowd for both of us. We had given them a good

fight.

Football - We had a six man football league.

Hutchinson was our quarterback and I played end. Red could really throw

a pass and I was able to catch them. We won the league. It was tag

football but blocks were allowed. The games could get a little rough but

it was good exercise.

When I arrived, there were only the south and north

compounds. The south compound was for the British but several hundred

Americans were in that compound. As the north #1 filled up with about

2,000 men, the north #2 was built. When north 2 reached 2,000 men, north

3 was built. I am pretty sure that north 3 also held 2,000 men. All of

these were officers totaling about 6,500. Toward the end of the war, the

enlisted men came in and were housed in the area labeled enlisted area.

They had come in from camps in either or both Latvia and Lithuania which

was being overrun by the Russians.

When those enlisted men arrived, they were tired and

hungry. We did not have very much food ourselves but a collection was

made and food and some other items from our personal supplies were made

available to the enlisted men. Sometime later, I heard that the enlisted

men were complaining that they were not getting as much rations as the

officers got. They received the same rations. There may have been some

misunderstanding because several of the officers had managed to save

personal items which had been mailed from their families.

We all pulled duty as KPs (kitchen police). I was on

the roster about three times. We spent the whole day peeling potatoes

and turnips and cutting away the bad cabbage. Since we had to do that

only once every 150 days, no one complained.

Speaking of food. When I first arrived at the camp,

we each received a Red Cross parcel once a week. The parcel usually

contained a can of powdered milk which we called Klim. There was (you

may say were if you wish) a box of raisins or dates. a D-Bar which was a

chocolate bar, six packs of cigarettes, a can of Spam, some coffee, and

a small can of liver patê.

The parcels along with the German supplied potatoes,

turnips, cabbage, bread, barley, and beet sugar, served us adequately

for a couple months. Then things got a little worse. The parcels started

to come in once every two weeks and then one parcel for two men and then

hardly any at all. Those parcels, which did arrive now, showed signs of

having been opened and quite often, there was no coffee and fewer

cigarettes. During the decrease in parcels, there was also a shortage of

food from the Germans. Following D-Day, there was very little movement

of supplies. The heavy bombing and the low level strafing kept the

trains and trucks from moving during the daytime. I understood that the

parcels were shipped by train from Switzerland, which was a long way

from our camp. After the Battle of the Bulge, we started to feel the

pangs of hunger. Being hungry was not as bad as the lack of proper

nutrition. Our breakfast consisted of a bowl of barley, which was cooked

up in the kitchen of the mess hall. The best way to eat the barley was

to not look at it. A barley worm looks very much like a piece of barley

even when it is cooked. So if you did not look, it was very good.

Occasionally we had meat but the boys in the kitchen - some of whom had

been butchers in civilian life - said it was horse meat. I weighed about

170 lbs when shot down and when the war ended, I was down to 140 lbs.

One day we noticed that the Germans were erecting

another building across the street from our barracks. Naturally since we

had nothing else more exciting, we spent quite a bit of time watching

the construction. It looked very much like our barracks. After

completion of the building, we watched the Germans carry several boxes

and bags into the building. Then we noticed that some of the boxes were

marked with the symbol for dynamite or explosives. A building just

across the street loaded with explosives seemed just a little dangerous.

One day and order came down stating that almost everyone in our barracks

would be required to move to another barracks wherever we could find a

vacancy. I moved into a room in the barracks where my Bombardier lived.

Another order followed the first one. This one required all the Jewish

men to move into our former barracks. On our dog tags we had P for

Protestant, C for Catholic, and H for Hebrew. There is not much doubt

that the Germans figured that if the explosive loaded building ever blew

up, several of the Jewish men would go with it. Fortunately that never

happened.

Clothing

As for our clothing, we tried to salvage and maintain

the clothes we were wearing when we were captured. The Germans did issue

some very large and heavy coats to be worn in the winter. The

accompanying snapshot shows several members with their American

uniforms. The one in the upper left is our bombardier who I think was

born with a tie on. The person on the left in the front row was Gilbert

"Shorty" Klaeser who spoke fluent German and one day almost walked out

of the camp. Unfortunately he was recognized by one of guards and forced

to return. I believe these men were my room mates in the second room

that I lived in. I recognize Logan, Wallace "Chief" Tyner and Levins.

From left to right - Back Row - Irving

Day, P. J. Kiefer, Unknown, Brown, Andrew Logan, Wallace Tyner, Bush

Front Row - Gilbert Klaeser, Albert R. Johnson, Quinn, Earl Bason,

and William Levins

Dental

I think I can best describe our dental facilities by

recounting my experience. I developed an abscessed tooth, which started

to be very painful. Our dental clinic was in the south compound and had

three dentists who I believe were captured in the Anzio beachhead. When

I finally arrived at the dental clinic, my jaw was slightly swollen. The

dentist said the tooth would have to come out. He asked if I would like

some anesthetic. Then he told me that it would not do much good because

it was so weak, it was practically useless. We decided to forego the

anesthetic. He then started to loosen my tooth. Then he proceeded to

pull it. Suddenly, he stopped. I asked if the tooth was out. He said

that he hadn't pulled it yet. I asked why. He said that I was about to

pass out. I told him that I didn't care if I did pass out but to go

ahead and pull the tooth. He did pull the tooth. I asked why he thought

I was going to pass out. He said that he was watching my pupils, which

had gotten very small and indicated that I was about to pass out. Many

years later, I went to a Veterans Administration dental clinic to see if

I could get dental care. I was told that if I had dental work done while

in prison camp, that I could have work done on that portion of my mouth.

The VA said they would send for my records. I knew there were no records

kept of that work so I figured I would not get the care. A couple weeks

later, I was informed that they could work on the upper left part of my

mouth. They actually knew which tooth had been pulled. I was amazed but

later remembered that when we had been returned to the United States, we

were taken to a dental clinic and given a complete examination.

Evidently, I told the technician about the incident. Then later on, the

VA decided to work on the teeth of prisoners of war if they had been

detained for 6 months. And I think there have been changes since then.

As it is, I have had all my dental work done by the VA and fortunately,

I have had excellent care. Just recently, I had a 1½ hour root canal

without anesthetic. The tooth was dead so there was no need for the

anesthetic. Dr. Christian is an artist.

Our band and the fire

We did have a band and the musicians did a good job

of entertaining us on holidays and during the supper meal. We had a

pretty good vocalist. As I remember, we had a piano, drums, trumpets,

trombones, saxes, and strings. There were actually two bands. One was

the classical and the other was popular. And of course our comedians

were usually there to keep us laughing. Oddly, I don't remember anything

about the fire except that the mess hall where the instruments were

stored caught fire and when it cooled enough to search the debris, all

of the brass instruments were found flat and I am not talking about the

pitch. They had melted. Fortunately the other compounds had instruments

and our band was formed again. That band did a lot in keeping the

spirits up.

Hot Water Brigade

After the morning roll call, several men from each

barracks had the duty of getting the hot water for morning coffee in

each room. I was one of those who stood in the ranks with my bucket

waiting for the command "Dismissed!" On the dismissal command, we would

run toward the gate that led to the mess hall. During roll call, the

gate was closed and guarded by a German soldier. From experience, he

knew that he had to open that gate as quickly as possible because there

were about 40 men running toward him at full speed. It was imperative to

be one of the first in line because there was just so much water and

only the first 20 men were sure of getting their portion.

On this particular morning, it was cold and snow

covered the ground. Compounding the situation was the fact that the

gates opened inwardly. For some reason or other, the guard was a little

slow in opening the gates and unfortunately was standing right in the

path of the thundering herd. Down he went along with about 10 of the

runners. It was a snowy mess. I only wish someone could have taken a

movie of that because it would have made a great scene. After that, the

guard opened only one side of the gate and stood well to the side.

Guard Dogs

All the dogs that I saw were German Shepherds. After

we were confined to our barracks for the night, the dogs were allowed to

run free in the camp. We had an officer who lived in our barracks but

not in our room. He was a very attractive man. Stood over six feet tall,

blonde and well built. Also very affected. He wasn't very well liked by

the men in our room but would occasionally come in to talk. I don't

think he was well liked in his room either. One evening he was in our

room sitting on the window ledge telling us how great he was. I don't

know what prompted him to get up and leave the window. He was very lucky

because a dog had seen him and attacked at the very moment the guy

moved. We all saw the teeth and heard the snap, but the dog missed. We

laughed ourselves silly and Pretty boy did not come into our room after

that.

In the summer, the guard at the gate would be

accompanied by a dog. We, while we were standing in roll call formation

and being crazy Americans, would taunt the dog. Of course the dog would

bark and growl and pull at the leash. One day the dog broke away from

the guard and came charging toward us. We all faced the dog with

intentions of tearing it pieces. Evidently the dog sensed the situation

because he slid to a stop, put his tail between his legs and slunk back

to the guard. Then we felt sorry for the dog which got a severe beating

from the guard.

Goons

We called the guards "goons". When a guard would

enter the barracks, someone would holler a warning "Goon up".

Occasionally a guard would ask "Was ist der meaning of "goon". We

explained that it meant German of Noncommissioned rank. That seemed to

satisfy them.

NOTE ---- For the youngsters. In the comics of those

days there was an awful looking creature called a goon.

Booze

Yes, we had booze. Barrel staves were made from the

wood slats of the beds. The German bread made a good paste for fitting

the staves together. Then with the fruit from packages and beet sugar,

the brew was made. It was allowed to ferment and the alcohol was drawn

off. There were some very ingenious stills in the camp. Sometimes

potatoes were used. I can honestly say that not very many of the

prisoners drank brew. HOWEVER -- The room next to ours decided to make a

batch of booze. One of the men in that room was named Koch. He was not a

drinker and decided to abstain. They knew that with 15 drinkers, there

would not be much booze to go around. So, they elected to allow the

fermentation to go a little longer than the usual recipe called for.

Finally the day arrived for the party. Several of us tried to get a

taste of the booze. We were turned down. That night they had their party

and it was a lulu. We had to sit there and listen to them having all the

fun. The next morning, their room was a mess. Poor Lt. Koch had his

hands full. Hardly any of the drinkers could walk and several had fallen

out of their bunks. The room was filthy and smelled to high heaven. It

was two days before most of them recovered enough to walk.

Tunnels

One morning, I looked out the window and there on the

barbed wire fence was a cross and on the vertical board was an arrow

pointing down. On the horizontal board was written "Congratulations

#100". So I assumed that the Germans kept track. That particular tunnel

came from the room next to ours. A tunnel could not be dug deeper than 8

feet because of the underground water level. And once you got that deep

and started to dig in the horizontal shaft, you could go no farther than

eight feet because of lack of oxygen. We made use of the empty tin cans

to construction an air delivery system. The air would be piped through

the connected cans to where the workers (moles) were digging. Bellows

were used to force the air through the piping. One room had pedals

hooked up to run the bellows. The digging was also done with cans. The

sandy soil made it easy to dig but also dangerous. Many a bed slat went

into the construction of tunnel supports. Getting rid of the sand was

another problem. There was so much sand stored in the rafters, that we

were afraid the building would collapse. Sand was flushed in the toilets

but that had to be stopped because the toilets would become plugged.

Sand was loaded into trousers and we would walk around the camp

gradually letting the sand fall to the ground. None of these systems

worked very well because the Germans would send their ferrets (German

soldiers) under the barracks at night and they were very good at

discovering new tunnels which were eventually filled with barbed wire

and sand. If a tunnel reached 20 feet horizontally, that was considered

to be a fairly good attempt. To my knowledge, only one tunnel worked and

that one was dug from the British area, went under a German building,

and was very long. The Germans did not expect a tunnel to be attempted

in that manner. The escapees were captured very quickly.

I'll be back later to write some more when I find

time. ...

Sterling Tuck at 84.

Click here for

Sterling's personal website. |