|

By Judith Cameron:

My father,

Captain W. M. Nichols, landed in France on 13th May 1940. He

was part of a brand new venture, a mobile neurosurgical unit to be

deployed at the front for the first time in warfare. After a brief two

weeks in action this unit was cut off by the German advance at Krombeke,

not far from Dunkirk, while still struggling to deal with 800 wounded.

The medical officers and wounded men were sent to captured hospitals in

France and Belgium.

|

Dr. Nic |

From there Captain

Nichols and his unit were sent to a group of new prisoner hospitals in

Thuringia, and he began work there in October 1940. He was frequently in

trouble with the German authorities (he had been court-martialled for

the first time within a few days of capture, while still in Belgium) and

was moved round a number of hospitals as a result - Hildburghausen, Bad

Sulza, Molsdorf, Rotenburg and Egendorf. He made many friends at this

time and took a full part in the events of camp life. His letters

describe the amateur theatricals (his transformation into a glamorous

young woman), the sports ( cricket played with a ball of socks and a bat

of a “young tree”), efforts to learn the violin from a tutor who spoke

only Serbian, the parties, the Christmas meals, the library books (in

one place he read 50 books in a month). All this is told in a highly

entertaining style calculated to reassure his anxious family at home.

In the first week in

January 1943, after yet another falling out with the authorities, he was

sent to Stalag Luft 1, Barth, Pomerania, to be Camp Medical Officer.

What he found there was at once disappointing and a great relief. There

was no hospital and no surgical work, but the German camp staff was

helpful and reasonable, and the camp numbers were small, only about 300.

At first he was the

only medical officer there, but the camp grew very rapidly and after a

year, he begged for help and a senior officer was sent to take over.

Basically, Captain Nichols was a surgeon and though RAMC personnel had

to turn their hands to anything, a physician and a dentist were also

desirable. Col. Hankey (also captured in 1940) was both - a physician

and a dentist. The two men got on well and made a good team. By the end

of 1944, they had 5 doctors, about 6000 POWs and a hospital. A

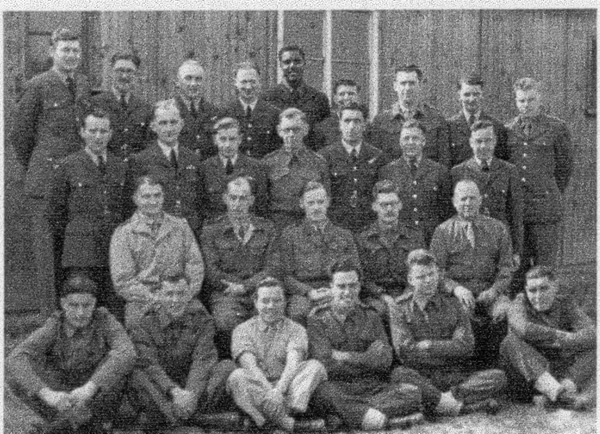

photograph in 1945 shows about 25 medical personnel, including

orderlies. The camp numbers had risen by then to over 9000. The effort

involved in obtaining essential facilities was unremitting, and the

result of hours, days, and months of arguing, pleading, persuading and

even bargaining with the authorities.

Medical Staff and volunteers in 1945 -

Dr.

Hankey,2nd row,3rd left; - Dr.

Nichols,2nd row,4th left; -

"Bunny"

Fogell, front row, 2nd right; - Smythe,back row,5th

left |

A

medical officer had certain advantages over his comrades. Firstly, he

had a job to do; technically, he was paid; technically he was not a

prisoner of war, but was in a category described as “detained

personnel.” Of course this meant little in practise. Secondly, he was

working for his own people, infinitely preferable to forced work for the

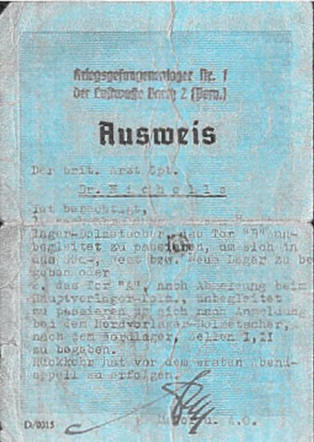

enemy. And thirdly, he had much more freedom of movement than most other

POWs. Nichols had a pass which allowed him to visit all the compounds in

Stalag Luft 1; he accompanied wounded or sick patients to Stralsund,

Neubrandenburg, and Schwerin for hospital treatment; in Thuringia, there

were inoculation clinics to run in work camps round the country; and

there were regional meetings twice a year to present cases for

repatriation . All this brought him in contact with many German

officers, guards, and even occasionally civilians.

To begin with,

in Stalag Luft 1, Capt Nichols had to operate in the most primitive

conditions. He describes his first appendix operation, using improvised

instruments – pot handles and pokers, sterilised in pots and pans on the

barrack stove. In “POWerful Memories”, written by Augustine Fernandez,

there is a vivid and affectionate description of such an operation from

the victim’s point of view! In “Behind Barbed Wire” by Morris Roy, the

doctor is described as a “ dynamic and energetic personality”, and he

took pride in making good the shortcomings of prison life, protecting

his patients and boosting morale whenever possible. He relied on

volunteers to help with the nursing and trained many non-medical

assistants who became extremely efficient as anaesthetists and operating

theatre staff. He spoke highly of the dedication of these men, many of

whom had been patients themselves.

|

Personal Identity Card and Camp

Pass of Dr. Nichols |

Nichols had made

friends with the German doctors in the camp, and they greatly assisted

him to equip his little hospital. One of them, Dr. Gunther Obst, gave

the anaesthetic for that first operation (illegally, as permission to

assist had been denied by Obst’s superiors). The two men became firm

friends. Dr.Obst spoke good English, and they had many interests in

common. They shared their enthusiasms, talked of books and mountains,

languages and music, admired photographs of each other’s families, and

dreamed of life after the war. A favourite daydream was to own a car

with a radio, so that you could enjoy the freedom of the open road

across Europe while listening to Bach at the same time – a dream in the

realms of fantasy in 1943. Obst would unobtrusively admit Nichols to the

German Officers mess to listen to concerts on records, and on at least

one occasion took him to the Marienkirche (the church that could be seen

from the camp) in Barth to hear the beautiful

Buchholz organ which he played himself. Nichols was introduced to Obst’s

fiancée, Ruth. Invitations to concerts were also issued by Oberst

Scherer, the camp commandant, and the head of security was also a music

lover, which indicates that at that time the officers of both sides were

on good terms.

Doc Nic tells how

the German doctors conspired with him to go out with a lorry at night

and steal a whole X-ray plant from a disused hospital. “The only

drawback was that we couldn’t give away our theft by indenting for new

X-ray film and I had to screen everything, drawing what I saw on paper

in the dark”. This happy state of affairs was not to continue for long.

Perhaps an officious Nazi began to complain about the co-operation, or

perhaps the two men were not circumspect enough even for a sympathetic

commander like Scherer. Dr. Obst found himself in serious trouble and he

was dismissed from his post and transferred to Stettin as a disciplinary

penalty. Dr. Thomas Obst, Gunther’s son, thinks this took place at the

end of 1943 as a direct result of assisting at the appendix operation

against orders. This date is well before the major purge of German

officers, including Scherer himself, which took place at the end of

1944. Obst’s name does not appear on the list of officers who were

dismissed with Scherer. Nichols writes in home letters of German

officers assisting in operations in May ’43 and again in September’43,

but he does not name them.

Even before his

arrest, Dr. Obst had become unwell. Perhaps because of this, he was

never brought to trial, and was transferred to hospitals as a patient,

and then back to his home in Halle as his health deteriorated.

Nichols’ work grew

with the camp. At first he had been active with the orchestra, the

plays, much reading and giving lectures, but as more and more American

flyers arrived in the camp he had no time for all of these recreations.

He took up swimming and fencing in an attempt to keep fit, fighting up

and down the wards and over the beds with one of his orderlies, a man

called “Bunny” Fogell – loud cheers from the poor patients as they

hacked and lunged at each other Musketeer style!

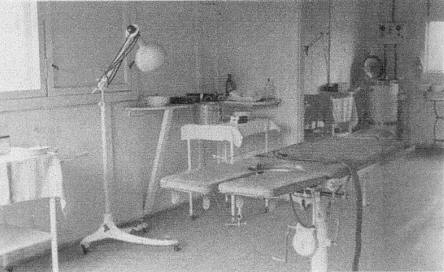

The workload now

might include 100 patients a day on sick parade, and there was an urgent

need for a new, or extended, hospital. After months of designing and

planning, this was completed in November 1944, and there are photographs

of a visit by a German General, who was delighted to see such a

civilised enterprise in this remote camp. An absolutely essential

refinement to the new surgical theatre was the acquisition of linoleum

for the floor. The floorboards of the hut were so ill-fitting “ that the

Baltic sand simply spouted up when the wind blew, and covered equipment

and patient in a gritty layer.” Before linoleum, “one did not operate

when the wind was in the East.” By constant badgering and cajoling, a

proper operating table, steam steriliser, and lamps were requisitioned

to complete the workplace. In spite of this improvement, however, there

were never enough medical supplies in the way of drugs, instruments and

dressings. Nichols had to fight for every bit, and 80% was provided by

the Red Cross, along with vital invalid food. The linoleum came from the

Swedish YMCA, whose representative was part if the IRC Association’s

inspection team.

|

Operating Room at Stalag Luft I |

Descriptions of surgical

procedures include hernia, appendix, many American football accidents,

and wound surgery. Of the two prisoners shot by the camp guards, Lt

Wyman was moribund before he reached the hospital, but Nichols kept in

touch after the war with George Whitehouse, the South African officer

who survived. He sent me a copy of a children’s classic, “Jock of the

Bushveldt”, which I still have.

The last few weeks

of the war and the two weeks which followed, were hectic. The medical

officers were fully stretched dealing with the poor creatures found at

the local concentration camp, as well as preparing the hospital for

evacuation and also some work with the civilian population in Barth

(including a maternity case). At home, Martin Nichols never spoke of the

concentration camp and his work there, preferring to retell the many

stories of amusing or unusual events that took place during his 27

months at Stalag Luft 1. The Senior Allied Commanding officer, Colonel

Zemke, tells the story of honouring an obligation to three German

civilians by smuggling them out with the wounded. These girls were on

the camp staff as secretaries and translators, had been helpful to the

prisoners and quite probably faced ‘a fate worse than death’ if left

behind at the mercy of the Russian army. The Russians absolutely forbade

the removal of any German citizen, but Nichols and Hankey disguised them

in nurses’ uniforms, and they flew to Britain with Nichols on 13th

May 1945, exactly five years to the day since he had set foot in France.

On

arrival, Doc Nic had to endure a good deal of teasing about bringing

home not one, but three German women! The girls were eventually

returned home to Germany, not knowing what they might find.

Miraculously, their homes and their families were still there to welcome

them. Ursula and Irma were to remain friendly with Martin all his life.

When, in 1958, the family visited them in Germany, it was obvious that

they regarded Doc Nic as somehow personally responsible for their safe

return. We were made wonderfully welcome.

Martin

brought home with him a mass of drawings, photographs, and other

memorabilia, which became part of our childhood, as well as the many

stories of his adventures. When I went with my brother and sister to

visit Barth in 2005 to meet up with POW survivors and their families, it

was the first time in our lives that we had met other people who shared

these same stories and pictures – a most moving experience.

|

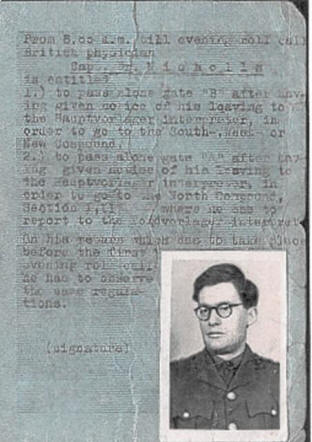

Dr. Gunther Obst |

Perhaps the most precious thing he brought back was his continuing

friendship with Gunther Obst. After the war, Gunther was able to get in

touch with Martin, and the letters from Germany make for very difficult

reading. Conditions there were quite terrible, and jobs almost

impossible to find. That a highly trained ophthalmologist like Obst was

driven to plead in his letters for darning wool and tobacco gives only

the smallest indication of the situation then prevailing. The Obst

family escaped with many starts and alarms from the Russian zone, but

his circumstances were not much improved. In poor health, and without

political influence, he had little chance of a permanent job. Desperate

for work and security, people would do almost anything and trample on

anyone to achieve these things. Martin looked for a post for Gunther in

Britain through the British Council. He was told that hundreds of people

were trying to do the same thing for their German friends. Eventually an

opening was found, but it was too late; Gunther was too ill to take it

up. He died in 1952, aged 40. By that time, Martin did have a car,

though not the sort that sported the luxury of a radio, and he visited

Gunther in a hospital just a few days before he died.

Dr

Obst’s son Thomas, has been in touch with the Nichols family most of his

life, and he came with us on our historic trip to Barth in 2005. We feel

that we share with him a significant small part of our fathers’ lives,

and through both these courageous men, we lay claim to the defining

events of Europe’s recent history.

After

the war, Martin Nichols returned to neurosurgery and in 1948 was

appointed to the hospital service in Aberdeen, Scotland. There he set up

a new neurosurgical unit, which served the whole of the North-East of

Scotland, with satellite clinics in Inverness and Dundee. He was popular

as a lecturer on many subjects, and his encyclopaedic knowledge can be

ascribed in some degree to five years’ eccentric study in POW camps in

Germany. He died in 1979.

|