|

E-Mail and the Terrorflieger

|

by Verne

Woods

On the

Internet newsgroup, soc.history.war.world-war-ii, World War II battles are

refought, the FW-190 and the Zero face off in imaginary dogfights and the

Sherman, Tiger and T-34 tanks compete again for engineering supremacy.

Recently, when the forum took up the subject of the best WWII TV

documentaries, I joined the discussion with this:

" In

the mid-1980's NBC produced a documentary on the 8th Air Force entitled,

"All the Fine Young Men." Of the many TV documentaries I've seen

in which B-17s and the European air war were featured, this documentary

reflected most accurately the war that I experienced. Because I was there

as a participant -- a B-17 pilot with the 91st Bomb Group -- it's

altogether likely that my nomination of "All the Fine Young Men"

as the best WWII TV documentary is lacking in objectivity."

The posting

generated several responses, one of which presented me with the following

questions:

" Was

there ever a thought on what these bombs would do once they reached the

remote ground? Did you and the other fine young men ever consider

this?"

These I

judged to be rhetorical provocationís and therefore best ignored.

Otherwise, I had the option of posting a response to the newsgroup for all

the world to read or of replying directly to the questioner by E-mail. I

chose the E-mail option:

"No, I

must confess that I, nor any member of my crew, nor anyone that I knew

among the thousands of downed air crew members in my POW camp ever gave

thought to the ethics of our bombing and thus to our killing of German

civilians. But were we not in fact, as your questions imply, participants

in an immoral act? No, I don't think so. We lived in an ethical world that

you, judging by the very fact that you raise the question, would not now

be able to recognize. The past is indeed another country."

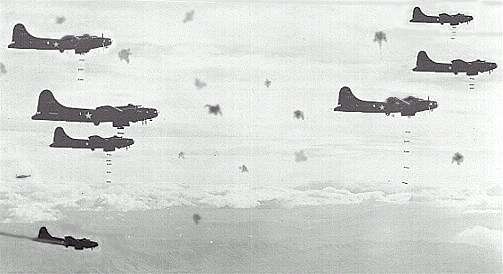

The terror in the

skies

over Germany

left very little time to ponder the terror wrought on the German civilians below

To this, my questioner, who identified herself as Erika replied:

"We

both inhabit that same past: you as an airman and I as a young child. You

delivered bombs; I was terrified of them." The word,

"terrified" had a resonance. To the German people, the air crews

of the RAF and the 8th Air Force were known as "terrorfliegers."

Was Erika's use of "terrified" an allusion to this idiom?

Intrigued by the possibility, I asked her: "Was I the indifferent and

immoral terrorflieger and you the innocent and terrorized child

below?" and I learned that yes, this was true.

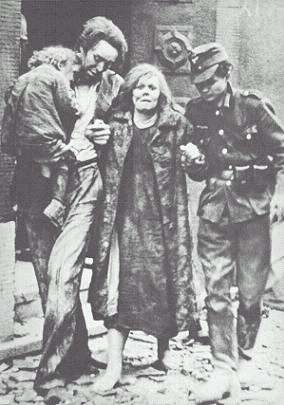

Dazed and in shock, a German family is

helped

from the wreckage of their home

Erika wrote:

"What

I do recall vividly is the droning sound of the bomber swarms high above

us. The terror was real."

In

resurrecting the long-dormant expression, "terrorflieger", in my

E-mail letter, I'd triggered the memory of a quite memorable wartime

incident which I related to Erika:

In early

May, 1945, after the Russian army had liberated my POW camp, several days

passed and no word reached us as to when we might be evacuated. As a

result, I and one of my POW roommates, in our impatience, took off for the

British lines a hundred miles away. On the main road west, we found

ourselves trudging along in a stream of German refugees who hoped to

escape the raping and vandalizing Russian army by reaching the relative

safety of the British lines.

On the

third day of our trek we overtook a young woman, her mother, and her

daughter of about six or seven. We fell in beside them. We conversed as

best we could with pantomime and mutually understood German and English

words. We learned from the young woman that her husband was last heard of

fighting somewhere in the East.

Before

leaving the POW camp, my roommate and I had packed Spam, D-bars

(chocolate), sugar and other food items from American Red Cross parcels.

Now that we were nearing the British lines where presumably food would be

provided, we decided that we should share our supply with the two women

and little girl. It's remarkable how food can elevate spirits and for a

brief while the five of us walked along as if on a carefree outing. The

young woman asked about us and we told her that we were kriegsgefangeners

from a stalag near the town of Barth. "Terrorfliegers!" the

young woman cried in mock anger, her little fists pounding my arm. "Ja,

terrorfliegers," we admitted.

A few miles

down the road, we came to a Russian check-point and my roommate and I were

passed through but our three companions were detained. When we left them,

the young woman waved good-bye, "Auf Wiedersehen, terrorfliegers."

In her

return letter Erika wrote that "I squeezed a little tear back"

because "both of us had been there." She told me that she, also,

when a little girl about the age of the child we'd met on our journey to

the West, had once found herself among a stream of refugees.

As so often

happens in E-mail correspondence with someone who only a short time before

had been a stranger, there is an initial rapport found in the sharing of

experiences, followed all too quickly, it seems, by a waning and an

unacknowledged termination. There seems nothing more either cares to say.

Thus it was with Erika and me. We never overtly gave expression to the

fact that our pleasant relationship was at an end. But it would have been

fitting, I think, even though a bit mawkish, had Erika ended our E-mail

encounter with the same words used by the young woman whom I had left

standing beside the road at that Russian check-point.

Write

To Verne Woods

|