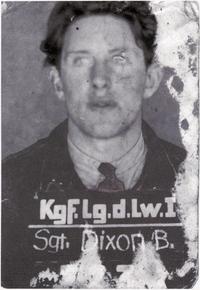

| Benjamin Dixon, born 3rd April 1921. I was

18 when the war started. I had been working for a jobbing builder firm

in Park Road called Suggitt. In June 1939 I looked in the

newspaper and found where the RAF Voluntary Reserve was recruiting for

wireless operators, air gunners, observers and pilots to join . So I

went down and they accepted me. Our headquarters used to be in the old

market in the caretakers room, and we used to go up twice a week for

practice. We used to do a little bit of Morse code and things like that

and they told us all about the sights for the machine guns and things.

Then we moved into Surtees Street, I think. There was a public house

there, the Volunteer Arms, and we were right across the road in a big

house. We were doing a guard duty outside and a bloke came running out

of the Volunteer Arms across the way and said “the war’s started!”

They’d just got the announcement at 11.

About two or three weeks later we got our actual call up. We all

amalgamated down the town. We didn’t have a full uniform. Some had a

shirt, some had trousers, some had a jacket – part of the uniform. Only

what they handed you out, so you took whatever there was for the time

being. We went to Prestwick in Scotland. We stayed on Prestwick

aerodrome and we got a couple of free flights on aircraft just to give

us practice. After about three weeks they posted us to Adamton House, a

big mansion right on the outskirts. A unit came from Scotland, and a

unit came from Hamble, down south. They converted the stables into

classrooms and we used to do our Morse and our theory down there. Then

we were posted down to Digby, a big fighter operational ‘drome. They

didn’t know what to do with us. They stuck us in this billet and nobody

knew we were there for a fortnight. Somebody found us and then they gave

us jobs washing up and clearing the runways of snow. We got all the jobs

that were going yet we were supposed to be trainee aircrew.

They put us on guard and we’d never even seen a rifle. Then they had

to take us and show us how to manage the guns. The chief armourer said

“I’ll take you every day and show you how to take the machine guns to

pieces and put them back together again. So we got a very good training

there. Then we were posted to Cranwell to do another radio course. Then

they sent you to Dorset to RAF Warmwell where we did our gunnery course

in old-fashioned planes called Harrows.

When we were down there the lads were coming back from Dunkirk. What

a pitiful state they were in. It gives you your first glimpse of what

war was like, seeing them coming off the boats. Then we went to Benson

and we had to do an operational training unit. You would go up with an

observer and a pilot and train as a crew. It was a way in to the

operational squadrons. Then we went to an operational squadron near

Nottingham, and they were Fairey Battles. It was a bomber aircraft like

a big version of a Spitfire. There was the pilot’s position and a

navigator could get in front and then there was the wireless ops and a

gunnery. It was open - you pulled your canopy back and then you were out

in the open air. We did a couple of trips then. The barges were building

up ready for the invasion so we used to do trips over there and bomb the

barges. It was only across the Channel and back, like, it wasn’t too

risky. We still got the flack and suchlike. I was a wireless

operator/air gunner.

They did away with the Fairey Battles and brought in the Wellington

aircraft. We were just about to go operational, flying in the

Wellingtons and I got posted. I got sent to a conversion course first at

RAF Finningley. I was supposed to practice on the Hampden aircraft –

never got on it yet. They were on circuits and bumps. They used to lose

quite a lot of people on circuits and bumps. What it was, they used to

train the pilot to take off and land at night, but he always had to have

somebody else with him, you see, so they used to take a wireless

operator or something like that. So if he went for a burton, you went

for a burton. Then they posted me down to Lindholme, and that was an

operational squadron, 50 squadron, actually it’s a well-known squadron.

Some of the Dambuster blokes were trained on there before they went onto

special squadrons. I joined this crew, we had two pilots, but one did

the navigation and one did the actual flying. There was the wireless

operator and the gunner, the navigator and the pilot in the Hampden. As

I say, I’d never been in a Hampden, they said “report tonight” and we

was on ops. Mind it was a reasonable one, the first one I did, we went

to the channel ports. We were getting one every third night or so. And

then we got one to go to Hanover and we did another one somewhere else,

then we got a trip to go to Bordeaux, the River Gironde.

We had to go down country to St Evals where the navy loaded us up

with the mines, cause we were going what they called “gardening”, laying

mines. We got to the mouth of the River Gironde. In those days we had no

instruments for navigating. You had to draw it out and take the wind off

and everything. The wireless operator could get a bearing out from

England, but when you got so far out, the signal didn’t go far enough.

So it all depended on the navigator. Anyway, we dropped the mine in the

mouth of the river and the pilot then said “we’ll go in and drop the

bombs” - there was like an oil works off the shore. Everything was so

quiet for a bombing raid, I never saw a ha’porth of flack come up or

anything. I think we must have been the first in. On the run in, all at

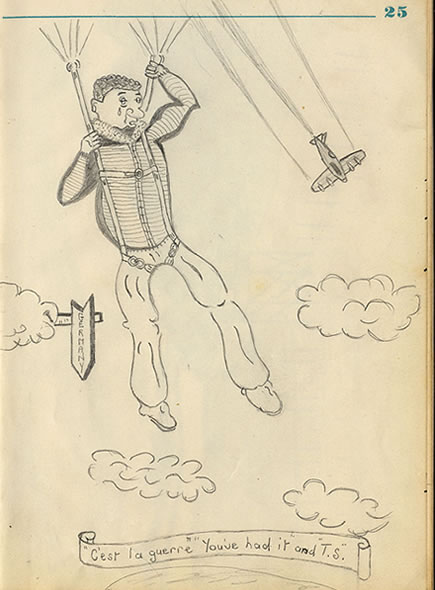

once there was a violent shudder. The wireless operator shouted “hello,

pilot, what’s the matter?” but we never heard anything so we thought

“there’s something up the creek now, like”. So the laddo (man) jettisoned the

hood at the back, but we couldn’t bail out cause we didn’t know what

height we were. Then all at once we hit – just a violent crunch and all

the aircraft just started to rip up and fires were going, everything

sparkles. All I could think of was “he hasn’t pressed that button to say

bombs gone”. Actually it was silly, because if they were going to go

they would probably go as we hit the deck. But I couldn’t get out until

he got out, he completely blocked my way. Cause the way I got in, that

had gone, all crunched up on the floor. So he started to get out. I

started to get up but my foot wouldn’t go. I pulled like merry blazes.

My flying boots must have been a bit bigger than I should have had, so

the one that was trapped came off. So he got out on the wing and I got

out. It was pitch black. We hadn’t heard from the lads at the front.

When I tried to walk off my leg just went. I had to crawl off the wing

and things were setting afire then, she was starting to blaze. I

clambered away about 25 yards from it. Couldn’t go back to help them – I

think they were dead in any case already.

We were in sand dunes. I sat there looking at the aircraft burning

and my leg was aching like merry hell. I couldn’t put it down at all. I

couldn’t see the laddo anywhere. Then I saw two Jerries coming across

with rifles. I put me hands up, I thought “I don’t want to get shot – I

can’t run away”. They weren’t very keen about being out in the raid, I

don’t think. They came over and dragged me along, they weren’t worried

about whether I could walk or not. We went to a Nissan hut, and there

was the other lad. So that’s how we got taken prisoner. Neither of us

could speak German. About half an hour passed and in came a big, tall,

slim German officer. He even had the monocle in his eye. You couldn’t

have got the more perfect example of a German. He could speak perfect

English. You can’t give them information so it was just a question of

who you were like. They sent for transport. I couldn’t walk and they

weren’t going to carry me so they got a wheelbarrow, put me in and made

the laddo push it to the cars! They put me in one car and him in the

other. They took me to a big house up the road and there was a medical

man who put a splint on me leg, and that eased the pain a good bit. He

actually brought me a bar of chocolate. There was a German guard about

my age looking after me, so I gave him some of it. I was there a few

hours then they took me to the Florence Nightingale hospital in

Bordeaux. Then the proper doctors did me leg properly. I had actually

broke the tibia and the fibia. The nurses were French (I couldn’t speak

French, either) and the Sisters were German. They looked after me and

let me write home.

I was taken from there by aircraft to Paris. On board there was a

young lad, a German fitter, and he’d broke his leg. We had a good talk

on the aircraft, the lad talked about his sister who lived in Oxford.

She would have been interred, I should imagine. He was a canny lad. Then

they took me to a great big hospital in Paris. It had all the big

swastika banners outside. On the way up, there was the laddo, and he

gave us a wave. They put me in a big room on my own. They were telling

me how they were winning the war. They would ply me with cigarettes on

the point that Dunkirk was just over and we had left all our cigarettes

in the trucks. So they had more Capstans and Players than we had! It was

all a means of propaganda. As I came out of hospital they took me for a

couple of hours to an Intelligence Headquarters, and there they

interrogated you and asked you what squadron you were with and what

target you were bombing and all this kind of stuff. Then they give you a

form, British Red Cross, and said “fill this in”. when you look at it,

it would say your name, number, date of birth and all that. Then it

would say “what is your squadron? Where did you fly from?” It was a con!

You didn’t have to be brilliant to recognise it was a con. They had put

it under the name of the Red Cross. I think they just tried it in case

you were under the weather you might do something silly like that. They

tell you stories and you are that bamboozled, you have to be so careful.

Then they sent me from there to Dulag Luft and there they put you in

a sweatbox. It was like a little room and they used to turn the heating

up, leave you overnight and interrogate you in the morning. But they got

very little out of people. I wasn’t there a week and they posted me to

the Black Forest and they put me in a convent. The nuns run it. It was a

big house with grounds. There I was convalescent with me foot, and in

there was one or two of our lads. We all used to sit at one big table to

have our meal, and they didn’t cook a bad meal, the nuns. There was a

Wing Commander there, he was only twenty-two. Every part of his body had

been burned. He had no ears, his lips had gone, his nose had gone, his

hands were webs. His body – here he had a tyre, where the fat had

rolled. How he survived – the pain alone must have been out of this

world.

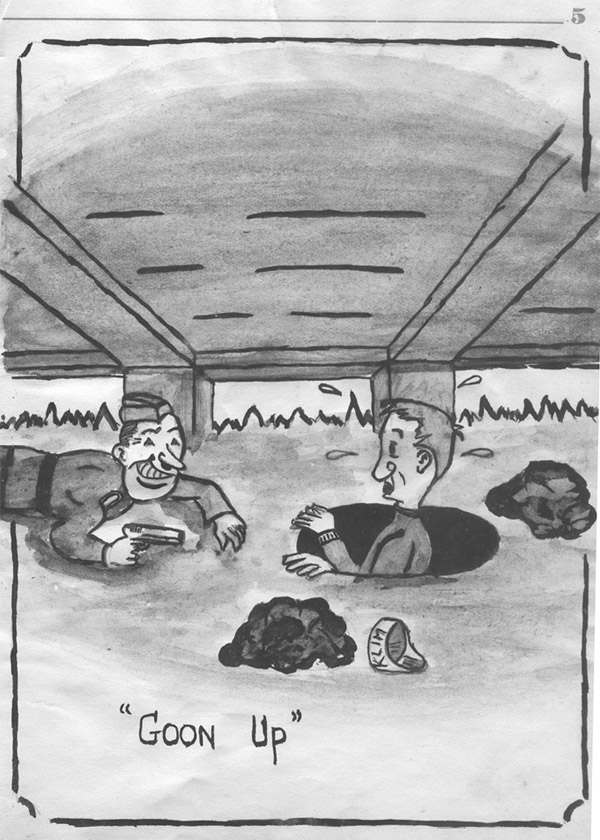

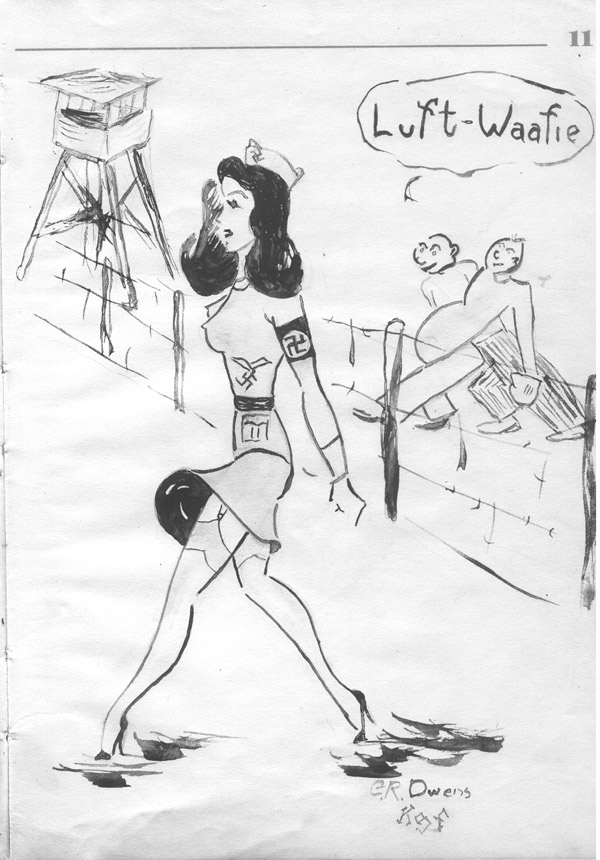

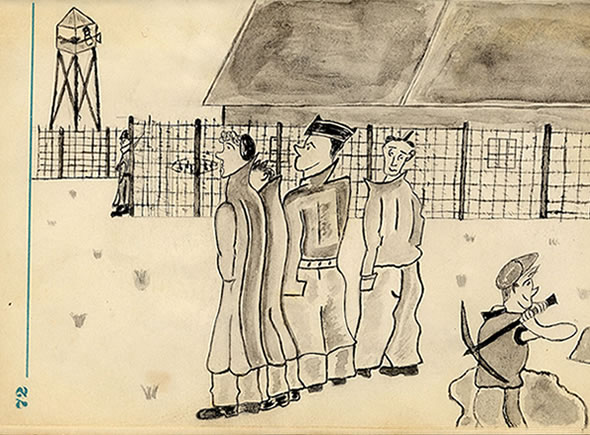

I was there a little while then we went to Stalag Luft 1. Then we

were pushed on cattle trucks and taken to Stalag Luft 3. That’s the one

where the Great Escape went from. But that was in the Officers’

Compound. We were in the Mens’ Compound. We were one of the first ones

to go to that camp. Then they asked for personnel to open up Stalag Luft

1 again. A lot of us had been at Stalag Luft 1 and we liked it. You

could see outside, not much but you could see outside, but Stalag Luft 3

it was just complete trees, you saw nothing but a forest. You never saw

the outside world, a horrible sensation. I was there about six months

and they brought out this idea about going back to Stalag Luft 1 and

there was about fifty or a hundred of us said we would go back.

Fortunately it wasn’t too bad because they stuck us in the officers’

compound and in there they actually had cold showers. Then I got a job

in the cookhouse, there was about ten of us with three big pressure

cookers and we used to cook for the whole camp. There was cabbage and

taties in the skins and a tiny bit of horsemeat. We had a German bloke

in charge of us to make sure we didn’t steal. Then they were going to

move all the NCOs again to a place right up near the Prussian border,

Stalag Luft 6 I think it was, but they wanted the cooking staff to stay

behind. I thought, “I’ve got a fair number here, I’m happy. You don’t

know what you’re walking into.” Some of the blokes weren’t very happy

that we stayed behind, probably because they never got the chance to

stay behind. It was the best move I ever made, because those lads went

to Stalag Luft 6 and when it was getting towards the end of the war they

evacuated that camp, they tramped down to the middle of Germany and when

they got there they tramped them back up again, our lads were strafing

them, the food was getting short and quite a number of them never

survived the journey. So I was glad I stayed.

Across the road from us, they had put the Russians in there. So when

they moved them out they had to decontaminate it, cause they used to die

like flies from typhus. We used to try and help them if we could, they

were in a terrible state. So then our officers started coming back into

their quarters and we moved back into our original rooms. Over there we

had no indoor wash facilities. We had to wash outside, the toilets were

outside as well. Then they started to bring the Americans in. There was

so many of them and they used to segregate the compounds, so there were

parts of the compounds and some of the Americans that I never saw. There

was about the ten of us cooks in this little room – we were cooking for

the Americans now as well. Eventually we got another five or six of

their NCOs came to help us cause there was that many, over about 8 000

in the camp then.

I was there for four years altogether in all the camps. The Russians

took it over when the war ended and the Americans came and took us out.

Typical Americans – we were the first prisoners of war in that camp and

we were the last prisoners of war to leave it. They took all their

troops out and we were the last to go. (Note from Ben - No offence

meant by last bit of story actually myself and roommates got on famously

with our American friends. Our room was visited regularly by them. ) |