| I, Charles C . "Tip" Clark, at the age of

82 years of age, am writing my memoirs as a former P.O.W. in Stalag Luft

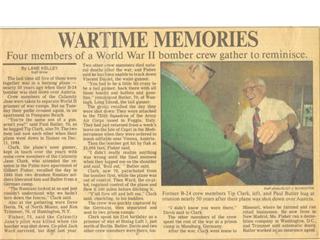

One. My P.O.W. # was 7470. I was T/Sgt. in Charles R. Campbell's

crew on B-24 Liberator. Shortly after graduating from high school in

Matthews, Missouri, 1941, at the age of 17, I enrolled in Draughn's

Business College in Memphis, Tennessee, and worked part time at cafes

and shoe stores. Later I got a job at E. I. DUPONT Powder Plant in

Millington, Tennessee. While working there, Pearl Harbor was bombed. Not

long after that I was drafted, and was sworn in at Jefferson Barracks in

St. Louis, Missouri. Very quickly, I found myself on a troop train

heading south. A person in charge came through as we traveled a ways and

informed us that we were in the Air Force. We arrived at our destination

at St. Petersburg, Florida, to start basic training; then, went to

Gulfport, Mississippi, for air-plane mechanic training. When I finished

there, I was given a 17 day delay in route to Las Vegas, Nevada, for

gunnery schooling. I returned home during that time. Finishing gunnery

school gave me a buck sergeant rating.

From there I was sent to Fresno, CA, and then on to Muroc Air Force Base

for overseas training and assigned to a crew of 10 men listed as

follows:

Charles R. "Chuck" Campbell; Ruport, Idaho; Pilot

Jack L. Ward; Los Angeles, California; Co-Pilot

David Davis; Columbus, Ohio (presently in Hollywood, Florida); Navigator

Kenneth Trimmer; Long Island, New York; Bombardier

C. C. "Tip" Clark; New Madrid, MO; Engineer and Gunner

William Devine; Pottsville, Pennsylvania; Radio Operator and Gunner

Vincen Daniels; New York, New York; Waist Gunner

Gilbert Fisher; Bethesda, Maryland; Nose Gunner

Andrew P. Kraynak; Pennsylvania; Ball Turret Gunner

Paul Butler; New York (later Connecticut); Tail Gunner

|

|

We were sent to San Francisco to be assigned to an airplane , which we

expected to be sent to the South Pacific. On waiting 30 days our orders

were changed. We boarded a troop train and traveled across the U.S. to

Patrick Henry, Virginia, and left there on Sept. 25,1944, on a French

Merchant Marine ship...arriving at Naples, Italy 14 days later. Our

menu, while on the ship going across, was boiled eggs and beans each

day. We were immediately loaded on a slow train to Foggia, Italy.

Traveling through wine country with orchards so plentiful, sometimes we

would jump off the train and pick some grapes, then jump back on. When

we arrived at Foggia about October 9th, 1944, was assigned our tent and

fed, we then began to get acquainted with our new surroundings. Our

bombing missions began pretty quick. We were never assigned a permanent

plane. It seems that we just got whatever plane that was ready.

Sometimes, we would have to change planes because the one assigned would

be red lined (grounded). I'll never forget our first mission.

We encountered pretty heavy flak (88 mm gunshots fired from the ground),

and when we landed back at Foggia, most of us jumped out and started

counting little places where we were hit. I think there were 57. We

never bothered anymore about looking. After flying 19 missions of which

several were double sorties, we began to get kinda flak happy (nerves).

Our pilot, Chuck, arranged for us to go to the "Isle of Capri" for one

week. It was the most beautiful place I ever did see -- except home!

On our first mission after returning to Foggia, which was our 20th

mission, we got a direct hit on December 11, 1944, over Vienna, Austria.

Our lead plane's controls were shot out and beyond his control, leading

us right back over the target after we had already released our bombs.

At this point the gun batteries on the ground had determined our range.

Being in the top turret, I saw the burst of flak coming. One, two,

three, and the fourth one got us, killing Chuck, our pilot; injuring

Jack, the co-pilot; and injuring the bombardier. No one else was hit.

Our plane was very much out of control. Jack was trying hard to bring it

around. At the same time, he gave me a hand motion to bail out. I got on

the catwalk and looked back; and he motioned me to come back. I got

about halfway back to the cockpit and he motioned me again to jump. I

didn't know that Chuck had been killed at this time. I looked back at

Jack again and he motioned for me to jump, which I did. Jack changed his

mind again and no one else bailed out. He turned on the automatic pilot

and gained control of the plane, which he couldn't do manually. We only

had one engine operating properly. One engine was running away, one was

feathered, and one was on fire. How long it was on fire, I don't know.

How far they flew before they had to jump, while high enough, is just a

guess. They caught up with me about five days later at Dulag Luft in

Frankford, Germany. In the meantime, I was in the dark. I had no idea

what had happened to them.

They informed me that on completion of everyone leaving the plane, it

was set to circle and plunge into the ground. Chuck, our pilot, went

down with the plane. As I said, our plane was hit on Dec. 11th, 1944,

and the 725th squadron was notified that our plane had been hit and the

plane had left formation and lost altitude. Only one parachute was seen

leaving the plane.

My parents were notified on Christmas Eve day that I was missing in

action. A telegram was delivered to my parents' home. My sister, Nadine,

went over to a small town nearby, Kewanee, Missouri, where my dad was

working on the roof of the Methodist Church, to let him know. My mother

had her hands full trying to calm my dad during this time. He took the

news so hard that he was having a lot of trouble handling it. She was

having to be strong for him, even with all her heart ache.

When I landed on the ground, I was greeted by 15 or 20 people I supposed

were slave laborers. They acted extremely nice, and one offered me an

American cigarette; but very shortly, four German soldiers, spread out,

came toward me. The people around me disappeared very quickly. I was

instructed to pick up my chute. We got into a convertible sedan and they

began trying to find out what to do with me. Not understanding German, I

had to guess about a lot of things. They took me to a brick school house

where they had an office. They made several phone calls trying to decide

what to do with me, "heiling" Hitler on the phone.

At sundown, two officers and a soldier ordered me to follow them. One

officer, I assumed, was a doctor. We marched down the street and

approached a high wall with many scars or peck marks, appeared to be

rifle marks; and I thought they were going to execute me. I considered

running, but knew if I did, they would certainly shoot me, so I kept

walking and waiting, expecting them to stop at any time; but we got to a

street corner and turned. I was quite relieved. Finally, they put me

upstairs in a room next to a patrol unit of about 8 or 10 soldiers. I

had a bunk with a little straw in it. They brought me a round loaf of

German bread, and gave me a knife with about a 4" blade to cut my bread

with and a bowl of soup. I only ate 2 or 3 bites. I just didn't have an

appetite. They changed the guards while I had this meal and didn't ask

for the knife back. I hid the knife on the bunk above me, thinking maybe

I might get a chance to escape that night. After considering my

treatment, thus far, I thought maybe they had planted the knife on

purpose to have an excuse to execute me, so I decided to turn the knife

over to the guard. He was quite surprised. I didn't sleep much that

night because he marched up and down beside my bed, clicking his heels

each time he'd turn around. They were always "heiling" Hitler whenever

they met anyone.

The next day, they put me on a 1 1/2 ton truck half loaded with tires

and about 6 soldiers; delivered me to a confinement in Vienna that had

18 American airmen who'd been shot down the same day as I had. They had

very little to do with me at first, thinking I might be a German planted

among them. The next day, being December 13, 1944, we were put on a

flatbed 1 1/2 ton truck, instructed to keep our head down, stay quiet

and still. I understood "why", right away. People along the way would

throw things at us, spit at us and, I assume, saying bad things to us.

Arriving at a train station, our guards had us to get in a corner, and

they kept their backs to us, facing the public to make them leave us

alone. Very soon, we were put on a train into two private rooms with one

guard in each room. We had no water or food; and needless to say, we got

very hungry and thirsty.

Where we went to, I have no idea. When we would get to a town, we

would have to unload, walk across town, load onto another train and

proceed, I think, to an interrogation center. I was put into solitary

and brought out at times for questioning at any time of night or day.

They threatened to stand me in the snow barefoot, turn me over to the

Gestapo or the SS if I didn't cooperate with them and tell them answers

to their questions.

Name, rank, and serial number is all I ever gave, which was by

regulations, all I was supposed to say. The questioning went on for

about two days. Our next stop was Dulag Luft at Frankfurt, Germany,

where all of my crew were reunited, with the exception of Jack and

Trimmer, who were sent to a hospital somewhere for treatment. I was

assigned to a room and upon my entrance, the first person I met was John

Payne of Memphis, Tennessee, (a personal friend I last saw in Memphis

before entering service). We spent the rest of our time together while

in prison, and we still stay in contact.

Dulag Luft in Frankfurt was a pool where prisoners were sent out to

different permanent camps. I had been there 3 or 4 days when someone

said they were gathering up a group to go to an officers' P.O.W. camp;

and that enlisted men could go. It was rumored that they had movies,

swimming pools, etc., which we didn't believe, but my crew figured it

would be better than here; so we signed up to go. Right away, we were

loaded into a prison car so full of P.O.W.'s that we had to stand

closely. I don't remember how many days we were on the trip, but as we

went to Berlin there was an air raid. The guards left us locked in and

they went to the air raid shelters. Thankfully, we were not bombed in

that area. We were so crowded , it was a miserable trip.

Arriving at Barth, Germany, we were ordered off the train and in

formation to march to Stalag Luft 1 near by. We had to march between two

mean dogs nipping at us. That was their introduction, I suppose. I'm not

exactly sure, but I think we were in the North compound. We watched them

train their dogs in the direction of the Baltic Sea. Incidentally, they

said we were only 60 miles from Sweden. There were around 10,000

kriegies (P.O.W.'s) at this camp. My stay at Stalag Luft 1 is pretty

well a story in itself. Colonel F.S. Gabreski and Colonel Hubert Zemke

were our commanding officers, and we thought very highly of them. They

had us organized in a very military manner. We were housed in barracks

with cracks in the floor. Sometimes a guard would crawl under our floor

at night and eavesdrop on us for information. A kriegie would heat some

water and pour it on him. I think you can guess what happened next. We

were always locked in at night. One or two guards with dogs would roam

around the barrack. Our windows were covered. No light was allowed

to shine through. If there was an air raid during the daytime, all

kriegies had to go inside and close all doors. I remember one kriegie

didn't know there was an air raid alarm and ran outside. A guard shot

and killed him. That was really upsetting to all of us.

We had a ration of potatoes and cabbage pretty regularly. We were

supposed to get one Red Cross parcel per person a week. The most I

remember ever getting was one parcel to four kriegies a week. Many times

we didn't receive any. The parcels contained many items: two packs of

cigarettes, one can jelly, D Bar (chocolate bar), powdered milk, salt,

pepper, prunes or raisins, and other items that I can't remember. The

pepper was confiscated because if we escaped we couldn't put pepper in

our tracks to keep the dogs from tracking us. All cans of food were

punctured with a hand axe, so we would not be able to pack an escape

kit.

There were details called out every so often to go just outside of

camp to get potatoes and/or coal to be distributed in our compound. Of

course, we would cheat and stuff our jackets with as much as we could.

Our barracks were made of wood with several rooms, with a hallway down

the middle. The bunks were built from wall to wall on one side three

bunks high; and slept 18 men. In a corner, another set, three high,

would sleep 6 men. In the other corner, we had a coal heating stove. In

our room we

elected two kriegies to prepare and distribute whatever food we had. As

you might guess, we watched them very closely to be sure some didn't get

more than others. We felt by preparing it all together, it would go

farther. Our loaves of bread would be brought in, unwrapped, in an open

wagon pulled by one horse. Malnutrition was common with all of us.

When we would first get up, we would black out for a few seconds.

After being locked in, we could go about inside our own barrack from

room to room as we pleased. If and when we would receive a news

bulletin, anyone in your room that didn't live there, had to leave. We

received bulletins from our secret radio often. Two kriegies would come

in and ask if our room was clear. We knew as soon as they came in who

they were, and we would tell anyone who didn't belong, to leave.

They would go to each room and do the same thing; so everyone would

get the news. They would tell us where the American, British, and

Russian fronts were, and how they were advancing, or other news such as

President Roosevelt dieing. At the front of our barrack was a room we

used as our restroom. It was equipped with a container for waste. The

next morning, two kriegies were detailed to carry the containers to a

designated place. These kriegies were called the "Honey Bucket Brigade."

Fortunately, we most always had plenty of soap and water. There were

quite a few paperback books; and we could play ball, box, pitch washers,

play cards; do lots of walking or creative things with what we could

find. We would flatten tin cans and make cooking pans. Some guys would

melt wrappers from food boxes, and pour into a wooden mold in the shape

of wings, etc. One kriegie made a clock out of tin cans and it worked.

There were men from about every professional background you could think

of: doctors, lawyers, ministers, accountants, etc. Men who played poker

and lost would pay off by writing a check. Were they good? Who knows?

Sometimes, a group of guards would storm our quarters, order everyone

out, and do a search: upsetting our beds, dumping boxes, really messing

up everything...trying to find our secret radio, weapons, or anything we

shouldn't have. They would also take whatever they wanted. If you

thought of an escape plan, you were to submit it to our escape

committee. They would decide if it was a good plan and who would be the

best to use it. If you wanted to try to escape, you were supposed to

submit your name, even if you had not submitted a plan. I don't know if

there was ever an attempt while I was there, but I don't think so.

Because it was nearing the end of the war could have been the reason.

Opportunities never cease. Some kriegies opened a business. They

assessed points on almost everything. There were so many points for a D

Bar, powdered milk, pack of cigarettes, a wristwatch, etc. We would

present our product for what they had and make our deal. One day a cat

got into our compound. The chase was quite interesting. The cat lost! I

didn't get any of it. There came times when we desperately needed a

shower. In order to accomplish this we would tell them we had lice. We

would have to gather up all our belongings, march down to a place where

we could put all our clothes in an oven; take a shower, then come out on

the other side, collect our clothes, and return to our quarters.

Sometimes, showers were available on request.

We would march down to the shower, get soaped up, and the guard would

turn off the water. For him to turn the water back on would require that

someone give him a cigarette. If we gave them more than one, they would

demand more the next time.

Some days it was extremely cold. Snow came down with the wind blowing it

crossways. You could depend on it; they would call out "roust" or roll

call. We would be in formation, and the guards could never count

right when it was cold; so we had to stand there in the cold until the

German soldiers sent for a list of everyone...then they could call us

out by name. After this we would be dismissed. On pretty days it was a

common practice for kriegies to pair off and walk around the compound

near the "warning wire", talking of home and everything imaginable until

it was time to go inside and lock up.

Along about April of 1944, news came that the fronts were moving fast.

We were told to dig trenches and prepare ourselves for protection. We

were also told that the Russians would be shooting from one side of the

camp and the Germans would be shooting from the other side. The night

fell and the Germans left about 10 p.m. to avoid capture by the

Russians. When daylight came, we were liberated by two drunk Russians in

a tank. Everyone seemed to know we were being freed. Orders were given

that everyone must stay put and not go outside the compound for fear of

stepping on mines and boobie traps. The two Russians were meeting with

Colonel Zemke, (who could speak Russian fluently), seemed unhappy that

we hadn't torn down the fences; so, the Colonel gave orders to tear them

down. Very shortly, several thousand kriegies were scattered out all

over the place, going into Barth and confiscating everything from milk

cows to motorcycles.

Late that afternoon, they began to come back to their quarters and build

little camp fires and cook things they'd found. A few of us thought it

best for us not go outside the compound until we could find out more of

what was really going on. After two days, Colonel Zemke appointed M.P.s

to get in towers and not allow anyone out. Our camp was on a small

peninsula and M.P.s were placed so no one could leave. About the 4th

day, Paul Butler... my tail gunner, Jim (somebody)...a friend, and I

decided to go out. We found a jon boat; paddled across to another

peninsula; and went into Barth.

We explored the town all day, just looking for anything. Late that

evening, a German with horses and wagon, hauling stray, came by; so we

just hopped on. We were tired. Shortly, a truck, with a cover over the

bed carrying several Russian soldiers passed us and stopped to remove

the wheels from a car that was parked. When they pulled out, we ran and

climbed in the truck with the soldiers. They were nice, and we swapped

some souvenirs. We must have traveled about 5 miles to a crossroad. The

truck turned to the left and after about 2 miles, the truck stopped. An

officer, I presume, got out of the cab, came back to the rear and began

talking to us in Russian. Not being able to communicate with him, we

decided to just get out. They pulled out and left us, and we started

back the way we came.

We noticed a group of about 50 people at a barn cooking something. We

were hungry so we just stopped and joined them. They fed us. Leaving

them, we began to walk and soon another truck passed us and was stopping

along the way to pick

up barrels. We ran and jumped on. A wild guess is that we rode it for

about 30 miles. It was getting dark. We got off the truck at the edge of

some rather large town. There was no one to be seen. It was deathly

quite. We didn't know what to think. A rooster crowed. Finally, we saw

someone a long ways off in front of us and standing in the middle of the

street. We approached him and informed him that we were American

P.O.W.'s and needed a place to sleep. He summoned someone, and he took

us up

about 4 stories to a bedroom. We asked for some food, and it was brought

to us. We noticed that this was their headquarters for that area; and

the town was under curfew. We were lucky we didnít get shot at.

We got up the next morning, went down to the street, and headed in the

direction we thought might be some Americans. Somewhere, we found little

map, which was a big help in showing us the direction to go. I do

believe the Lord was with us. We also found a little book with English

and the equivalent word in German. This was extremely helpful. I wish I

could tell you the route we took, but I can't. We walked; rode buggies,

one plane, a bus or two, and whatever came by. In our walking we would

be in marches with lots of German people moving away from being caught

under Russian rule. We would see a dead horse, and a hunk of meat would

be cut out of him. When we became hungry, we would look for a farmstead

with chickens and cows. There would usually be a man and woman looking

after things. They would claim not to have anything to eat and we would

pound the table and say "essen, yah" (eat, yes). We would start opening

cabinets and drawers and whatever we found...we would demand them to

cook it. Sometimes, they would and sometimes, they wouldn't. We never

abused anyone.

One evening, about sundown, we saw a good prospective looking

farmhouse, a little off the road, with some activity. We proceeded

toward the place, and just before we got to it, discovered it was a

Russian headquarters. We were a little puzzled as what to do. Talking

between ourselves, we decided to go on up to the house, identify

ourselves, and ask for some water, then leave. As we approached 3 or 4

soldiers, one was very drunk and said "halt." He pulled out his pistol;

began to lower it toward me; and another soldier near by jumped in and

grabbed him. I think he very likely saved my life. They let him keep his

pistol, but removed the clip and kept it from him. That introduction

being ended, we began to talk with them by means of broken English and

sign language. We were invited to their evening meal. We declined, but

they insisted; so we accepted. Inside their buildings, they had a long

table loaded with lots of food. There was plenty of meat, vegetables,

etc.

Of course, there was vodka. We felt it would be unsociable to them if

we didnít accept. We were not to hard to coax into it. They had German

civilians waiting on tables. As soon as we felt comfortable, we

excused ourselves, and told them we were anxious to go home. We found

a house on down the way. No one was home, so we just went in and spent

the night. Somewhere, on down the road, we entered a town, We

found out a bunch was gathering in someone's cellar, having a party, and

drinking up his stock of beverages; sooooo! we were ready to check it

out, since we were enjoying our freedom. Yep, we did it. We got

very "tipsey", which I'm not proud of, today.

Where we slept that night.....I do not remember. At some point, we

managed to be where there was some air traffic. We asked permission to

board, and told them we were trying to get into American occupation. We

were granted permission. Where we landed is beyond my memory; but we

were in American territory. Right after we departed the plane, it took

off. We asked if there was some way we could catch a plane to England.

They said, "Well, if you had stayed on the plane, that's where it's

headed." That was a little disappointing; so, we left there and

proceeded toward the English Channel.

Arriving at the English Channel, we discussed trying to board a ship, and

just go on home. After walking up and down the harbor, we decided that

might not be too good of an idea. We thought we might accidentally get

on a ship that was going to Japan. That idea was abandoned. We wondered

what to do next. We talked to people we met and asked questions, finding

out that all ex-P.O.W.'s were supposed to report to one of the camps

that was being set up for them.

There was Camp Lucky Strike, Camp Camel, etc. We agreed to go to Lucky

Strike about 3 to 5 miles out. As we walked, truck loads from our Stalag

Luft One began passing us. They had been flown in. Arriving at

Lucky Strike, we found much confusion. Someone said there was about

50,000 kriegies there. Spending about 24 hours there, we had a bowl of

soup after standing in a long line. We were supposed to erect our tent;

so instead, we decided to go to Paris.

The guard at the gate said we had to have a pass. We just laughed and

said, "No, no, we're free", and we went on by. Right away, we caught an

18 wheeler all the way to Paris. One rode in the cab, and two of us rode

inside where the refrigeration unit was...in the front of the trailer.

Paris was something else to us. Our eyes became tired from seeing so

much. That means we needed a pay day which was impossible. The Red Cross

was all we could come up with. They said, "Nothing doing." That wasnít

good enough for us. We tried other places and Red Cross finally loaned

us $50.00, which we did pay back later.

Cigarettes were just as good as money, usually better. Pigalle was

another part of Paris that was very familiar to all soldiers: German and

American alike. I don't think I'll say anything more about that.

We enjoyed about a week in Paris, and thoughts of home began to nag at

us. We read in the "Stars and Stripes", where they were asking all

former P.O.W.'s to report to camp, that a ship was waiting to carry us

home. We didn't believe it, but agreed to head back and get in line.

Back at Lucky Strike, we met our buddies from Stalag Luft that flew

back. We met up with Lt. Jack Ward, our co-pilot; and Lt. Kenneth

Trimmer, our bombardier. This was our first time to see them since

bailing out.....a very joyous meeting.

Our wait for a ship wasn't long.....not over a week. We boarded the USS

Admiral H. T. Mayo. Our captain, Roger Heime, USCG, did a magnificent

job of feeding us hospital rations; live entertainment, and putting us

safely across that big Atlantic in 7 days to New York. Immediately, they

transferred us to a troop train that didn't stop until it got to St.

Louis. We had a little briefing and was issued a 60-day recuperation

leave. I got on the Old Greyhound bus early and the next stop was in

front of my home at Matthews, Missouri, Hwy. 61. I was coming home so

fast I was afraid not to call first. Telephones were few and far

between. I called Mr. Al Daugherty about a mile from my home and asked

him to go over and tell my family that I would be home in a few hours.

As I write this, I can't help but cry.

I hadn't heard from home since our plane had been shot down, and didn't

know what to expect. I thank the Lord that everything was just fine. The

Greyhound stopped in front of my home. I got out and made a dash for the

front door. My mom, dad, and sisters: Evelyn, Nadine, and Ramell, were

there to greet me with open arms. My brother, Arlene, was still in

service in Alabama; brothers, Farris and Melvin, were at their home near

Cooter, Missouri. Home and family never looked so good.

As I write this on September 5, 2006, the rest of my crew have passed on

except David Davis and Gil Fisher. I pray this writing of my memoirs

will be accepted in the spirit that I have intended. I did no acts of a

heroic nature. I thank God for seeing me

through, that I might be a witness for Him.

|

|

|

|