|

JOHN H. BRYNER

A Grandson’s Perspective

Countless stories from WWII exist – my Grandfather's is but one. It is no

more or less heroic or important than others, but, as my Grandfather, his

story holds a special place in my heart and significance to my life - one

that should be shared.

By March of 1945, Germany should have conceded defeat. As the Allied Armies

were approaching the center of Nazi Germany from all sides, my Grandfather

was sent on his third combat mission to bomb the last of the synthetic oil

refineries at Ruhland, southeast of Berlin. He was the tail-gunner on a B-17

Flying Fortress based in Foggia, Italy - part of the 15th Air Force, Second

Bomb Group, 20th Bomb Squadron. On this fateful 22nd day of March, 1945, my

Grandfather’s B-17 was flying in the most vulnerable position, at the rear

of the formation, "low and last," better known as “tail-end charley”. On the

first approach the lead bombardier could not see the target because of

ground smoke so the lead pilot called, “don’t drop, we’re going around

again”. As the formation of 28 planes made a right turn to go around,

“tail-end charley” sagged back further from the formation, and pilot Ernest

Williams struggled to catch up and close in with the other planes. He had

made a fatal mistake, or the tired old B-17, #44-6440, just didn’t have the

power to keep up. It was noon. Bomb Squadron 20 of the 2nd Bomb Group was

attacked by a couple German ME-262 fighters – these jet fighters, deployed

late in the war were faster than any of ours, but their effectiveness was

hindered by lack of jet fuel and skilled pilots. Nearest to the attacking

planes and possibly in the best position to fire at them, his gun jammed,

and he was not able to fire at the approaching fighters. Other gunners

attempted to repel the attack and brought down one of the incoming jets.

However, his B-17 was hit by a rocket in the left wing between the Number 1

and 2 engines. The pilot lost control and the plane began to spin, falling

back to earth. The g-forces on Grandfather and his nine crewmates kept them

from parachuting to safety. There was no hope of escape.

The plane was now on fire and part of the wing broke off with one engine.

Luckily, this stabilized the plane long enough for my Grandfather to open

his escape hatch and parachute to safety. He and the plane plummeted to

earth on divergent trajectories and he could not see where it landed or if

any of his buddies made it. My Grandfather landed on soft ground in a German

field, near the town of Bückgen, in what was to become East Germany.

Immediately, he was taken prisoner by civilian authorities and a company of

Hitler Youth – not knowing the fate of his crewmates.

At the same time of his capture, the American Third Army was crossing the

Rhine and the First Ukrainian Army were probably less than 50 miles east of

his location. After the usual solitary confinement and interrogation routine

he was taken by truck and train to Stalag Luft I in Barth, Germany,

practically on the Baltic Sea. En route, he and nine other American POWs

were bombed once by a lone plane. They spent nights underground in basements

while RAF bombs were falling on Berlin. At one stop the airmen were allowed

to go to a soup kitchen operated by local women at a train station. It was

night and there was one chance to escape into the blackness while the guards

were not looking. Whether to run or stay with the group was considered. But,

after all, the war was nearly over. Then, too late, the whistle blew for

boarding and the fleeting chance was not taken. Probably a good decision.

In less than 50 days, Germany would capitulate. Yet, with very limited

resources, the German army resolved to carry-on (or was simply afraid of the

Nazi Party) and sent Grandfather to Stalag Luft I, a POW camp started for

British flying officers but later expanded to include Americans, hundreds of

miles from where he was captured. At one point, near the end, Hitler put out

an order to execute all prisoners, but his generals dared not carry out this

decree. Eventually, the POWs were liberated by the Russian Army. Although it

was against orders, some of the Americans went into Barth to investigate the

situation. Grandfather and another fellow found a boat and rowed across the

bay for a visit to Barth. He sat up on the roof at the town square and

looked down upon a musical concert performance presented by a professional

Russian orchestra. Later, he stumbled onto the flak school for girls, and

was startled to find one of the young girls hiding in a barracks. She helped

Grandfather pick up souvenirs from the abandoned living quarters such as

ration tokens, coins and a couple photos. They tried to talk, but the

language barrier was too much; it was getting late, and fear of the Russian

soldiers caused Grandfather to head back to the boat and row back to camp.

The Camp was held ransom for a week by Stalin but in May 1945 the POWs were

evacuated to Le Havre, France by 8th Air Force planes. It is hard imagine

what it must have been like during the last few months of the war, in a

German POW camp.

Shortly after the war, Grandfather married his 18-year-old sweetheart, Inez

Long from Virginia. He proceeded to leave the war behind and simply carry on

with his life. He was barely 20 and yet he was ready to get an education and

start a career. Using the GI Bill he went to college, eventually earning his

Ph.D. in microbiology. He went to work for the United States Department of

Agriculture doing research. In addition, he helped raise three boys.

Until the fall of the USSR and its satellites in the late 1980s, there was

no way for my Grandfather to learn exactly what happened to his crewmates.

In the late 1990’s he joined the 2nd Bomb Group Association to possibly meet

other airmen and do research on his crew. Independent of his research some

German historians near the town of Grossräschen, a short drive from Bückgen,

were doing parallel research.

Although study of WWII was denied by the East German government during the

cold war years, when “the wall” came down, East Germans were again able to

freely investigate their past or the past of their parents and grandparents.

One such individual, Peter Gajda, had researched the downing of my

Grandfather's plane - it was the only one in his area for which the

coordinates were precisely known. Peter’s father was a flak-gunner in the

German Army trying to shoot down allied planes like my Grandfather’s. He

stumbled onto the Bryner name. Peter met Eva Wessell who was visiting

Germany in 1996. As a five year old girl, she had lived just down the street

from the crash and is now a professor in California. Gajda asked Wessell to

try and locate my Grandfather through the 2nd Bomb Group Association. She

did so, only a year after he had joined.

John H. Bryner, examining B-17 wreckage in

Grossräschen, September 2001.

It was February 2001, after pieces of his plane were found, that my

Grandfather received a letter from the citizens of Grossräschen. They

invited him to visit and view the unearthed pieces of his B-17. He did so in

September 2001. Visiting with Gajda and local citizens who remember the

crash, he learned the full story of the fate of his crewmates. He met and

talked with some of the youth, now grown men, who were involved in his

capture at Buckgen.

Grossräschen is where his crewmates and plane crashed, together, on top of a

large house occupied by the rail workers of the town and displaced families

who had been bombed out from larger cities. These folk who were home might

have been sitting down for their noonday meal when the air raid warning

sounded. As the plane burned, local citizens desperately tried to enter the

house to rescue survivors, including the Americans, before the plane

exploded. Thirteen Germans and all nine of his crewmates were killed. After

the tragic day, the Germans buried the nine flyers outside the town by

Schmogroer forest. In 1946, after the war ended, the city reburied the crew

in the old cemetery, and erected a beautiful granite headstone. Not until

1951 were their bodies repatriated to the United States.

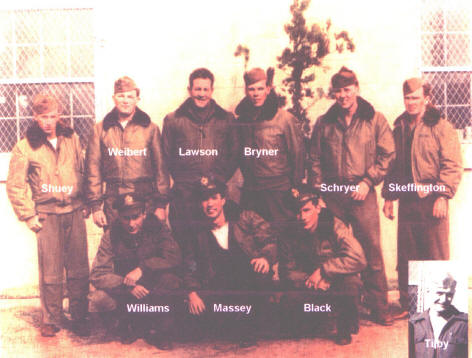

Williams Crew, B-17, 44-6440

I have yet to learn the names of the brave Germans; the names of the nine

B-17 crewmates who perished in the crash are: pilot Ernest H. Williams,

co-pilot Milas W. Massey, navigator John O. Black, bombardier Maurice A.

Tilby, upper turret gunner Clarence S. Weibert, lower turret gunner William

P. Skeffington, right waist gunner John C. Shuey, left waist gunner Conrad

R. Schryer and radio operator/gunner Henry C. Lawson. My Grandfather has

been able to contact living family members for all the crewmates with the

exception of Shuey.

This story, filled with awe and pride, of my Grandfather's experience in

WWII, is not over. The former American tail-gunner and the German son of a

flak-gunner are currently raising funds to commemorate the sixtieth

anniversary of the crash, with a memorial to honor not only the nine

crewmates, but also the thirteen Germans who lost their lives on that

fateful day. The Grossräschen City Council has approved the granite monument

and memorial dedication by a unanimous vote. It is to be erected in a place

of honor in the Grossräschen Center Cemetery. The dedication will take place

sixty years, to the day of the crash, on March 22, 2005.

Until then, they will continue to raise money to pay for the monument, to be

called the Peace Memorial Monument. In May, 2004, my father, Doug Bryner,

helped to raise a portion of the required costs via the ultra-marathon he

sponsors and manages, TIMTAM (This Is More Than A Marathon,) held every year

in Ames, IA.

UPDATE: The Peace Memorial Monument was dedicated on 22

March 2005 in Grossraschen, Germany, on the 60th year anniversary. to the

day, hour, minute of John's B-17 crash. John and 19 members of his

immediate family attended the ceremonies.

|