|

The

X organisation

is probably the area of undercover work that most people are

already

familiar with from escape stories. The

X

committee planned

escape

attempts, organised tunnel digging and devised other methods of exit

from

the camp.

The escape committee would usually try to

help any POW determined

to try an escape although it naturally gave most encouragement to,

those persons deemed to have the

best chance of success. For instance,

priority

might be given to persons fluent in

one of the European languages.

Next, there was 'Y'. That

section provided forgeries of maps, clothes and food, money and perhaps

a compass. It also organized a system of look-outs,

to protect the various undercover

activities.

Finally, there was the 'Z'

section. Activities included operation of the

camp's

secret radio. Probably most importantly, Z maintained contact with

the RAF intelligence section in

England by means of written codes.

All of the undercover work

will be described in considerably more detail, and to begin with, a

little more about the 'Z' section and its codes. In the earlier days of

the war, a few aircrew were given instruction in written codes in case

they were ever taken as prisoners-of-war. To improve

the obviously difficult security

aspect, such information was very

restricted, and it was suggested

that other aircrew might work out a code with their own family.

Fortunately, as things had turned

out, I had done that, having devised a code with my brother.

|

|

|

Tony Kilminster |

And this is the other half

of our private code team, my brother serving with the RAF in Africa in

1942. In the first letter that it was possible to write home, from

Stalag VIIIB, I was able to give my brother the details of how our

aircraft had been lost. The information was duly passed on to the

intelligence section of the RAF.

The vital part of secret

communication work, however, lay with the RAF codes. As soon as the 'Z'

section became organised at the new Stalag Luft I, it debriefed all new

POWs arriving in the camp, any useful items of

information being sent back to

England by coded POW mail. The information would be concerned mainly

with details of the loss of the new prisoner's aircraft so that,

provided a crew member was taken prisoner, the RAF would learn the

reason for the loss of that particular aircraft. Anything thought to be

of a military interest

that may have been noticed during a

prisoner's passage through Germany

would also be included.

Richard Drummond, one of

my fellow crew members and the second pilot of our ill fated Halifax.

Drummond had been one of the aircrew briefed in code work and, as a

prisoner-of-war, played a major role in the intelligence

gathering

and code transmission operations at Stalag Luft I.

|

|

|

Richard Drummond |

Code work has received

little publicity compared to that of escape operations;

in fact; codes are not even

mentioned in the official RAF history of escaping from Germany. However,

with the 'Cold War' at its height

when the history was first

published, that is perhaps understandable. It is only comparatively

recently that I have heard some stories about that area of secret work

myself.

One of the more-remarkable

tales about secret codes. A POW camp received a request from England to

find out the thickness of the armour on the then

new

German Tiger tank. Their first reaction was 'How do they think we can

find

that out from a POW camp'? The story goes that they were able to do just

that. They contacted a Polish national brought into the camp for some

maintenance work; he, in turn, was able to contact the Polish

Underground Movement, that organisation had people actually working in

one of the factories that made the tanks.

Stalag Luft I

Returning now to Stalag

Luft I, in addition to establishing the secret communications link with

the intelligence section in England, undercover

work

in general was soon under way and, for the time being, we leave the 'Z'

,

section for some stories about the 'Y'

organisation.

It was of little use an

escaper succeeding in getting out of the camp if he didn't have suitable

documents. Apart from checks at most strategic points such as railway

stations and major bridges, police and the Gestapo often made spot

identity checks, particularly on any form of transport, and an escaper

not adequately prepared would have been unlikely to survive any such

check. In most cases, documents had to be forged.

FORGERY

|

|

|

In the early days,

I only undertook forgery work after the huts (barracks) had been

locked and barred for the night; there was less chance of

interruption by German

security staff under those circumstances. To carry out the

forgery work,

a stool and something to serve as a small table were placed on

top of a larger table, so that the work could be brought as

close as possible under the none too bright electric light. A

blanket was draped over the window so that guards patrolling the

compound could not see through any chinks in the shutters that

were clamped across the windows at night. One of those earlier

types of forgery that has survived the years is described with

reference to the next two illustrations. |

| |

| Forged Identity Card

|

This is a forgery of a

German personal identity card, and it was the first

type

of forgery that I produced for the fledgling escape committee at

the new Stalag Luft I. It was actually copied from another

forgery that, to get us started, had been brought by the

volunteer group from Sagan when Stalag Luft I was reopened.

|

| |

The inside

of

the forgery. To begin with, these

forgeries were produced entirely by hand drawing. The example

here is one of our later editions, although still mainly drawn

by hand, the police stamps had proved difficult to fake

convincingly by hand painting and in this instance were added by

a

duplicating

process, a method described

later. The hand drawn parts of the forgeries

were produced using a brush and Indian ink. Fortunately, some

months before becoming the forger for Stalag Luft I, I had asked

for some art materials to be included in any parcel that could

be sent to me. Prisoners on both sides in the war were able to

receive a small number of personal parcels through the

International Red Cross. |

|

As just mentioned,

there were problems trying to imitate rubber stamps

convincingly.

In addition to hand painting, I had tried several ways of

getting

a more-realistic result.

This is one of the earlier efforts, it is

a

stamp

made by etching aluminum

with acid: the aluminum was cut from a camp cooking

utensil. One difficulty lay

in finding a suitable substance to act as an acid resist for the

design. Eventually, some cellulose paint was obtained from the

camp theatre

group and that proved reasonably

successful. After drawing the design on the aluminum with the

cellulose paint,

the background was etched down using hydrochloric acid, a

substance the camp

authorities had supplied to clean

the latrine. Metal Stamp

Metal Stamp |

|

SECURITY

Most POW

undercover activities had to take place virtually under the

noses of the roving

German security staff and to

protect that work, all huts had a 'Duty Look-out'. If a guard or

other suspect approached a hut, the look-out gave a shout of

'Goon Up'. All illegal activities would then cease and any

incriminating items would be hidden. The term 'Goon'

puzzled the guards

at first,

although they were pretty sure that is was uncomplimentary.

|

|

ARTS & CRAFTS

In between forgery

sessions, I was trying to teach myself the techniques

of

oil and water-colour painting. Although I made little real

progress and I haven't attempted any painting of that sort from

that day to this, those efforts

did have a use, and two paintings that have survived are

included here

to visually complement an aspect of the forgery story.

An oil painting of one of my

room-mates. however, to the story. During the longer days of

summer there was so little time between the huts being locked

and barred for the night, and lights out, that forgery work

necessarily had to proceed during open hours. To avoid having to

securely hide forgeries being worked upon every time German

personnel entered the hut, and that usually happened many times

during the course of a day, upon the shout of 'Goon up' from the

look-out, an unfinished painting was pinned over the top of the

forgery and I just carried on with the painting.

An oil painting of one of my

room-mates. however, to the story. During the longer days of

summer there was so little time between the huts being locked

and barred for the night, and lights out, that forgery work

necessarily had to proceed during open hours. To avoid having to

securely hide forgeries being worked upon every time German

personnel entered the hut, and that usually happened many times

during the course of a day, upon the shout of 'Goon up' from the

look-out, an unfinished painting was pinned over the top of the

forgery and I just carried on with the painting.

|

A water-colour that took its

turn in that procedure. Perhaps understandably, with a forgery

hidden underneath a painting, I became increasingly

uncomfortable if any German displayed more than a passing

interest in what I was doing. Some of the regulars must have

wondered why it was taking me so long to make progress on a

particular painting. |

|

On a somewhat similar theme, a POW arts and crafts exhibition, a

time when kriegie talents were put to more-legitimate use. Even

so, the abwehr, the

German security section,

must have been very intrigued, to say the least, by these

displays of kriegie work; many of the models required the use of

files saws or drills to produce them, all such items being on

the strictly forbidden list of course.

|

|

CONTRABAND

Whilst most

illegal articles were acquired by bribing or sometimes even

blackmailing a guard,

some items were almost impossible

to obtain in that way. However, some contraband was obtained

from England by being sent in

personal

parcels. Although all parcels were supposed to be opened and

checked by the camp security

staff, POWs were used as labour to unload the parcels from

railway trucks onto camp wagons, and to unload the wagons

again

at the camp. Parcels containing contraband would carry some

prearranged

distinguishing mark, and the attention of the guards could

usually be distracted for the brief moment necessary to

sidetrack a marked parcel. A number of items useful for the

camp's undercover activities were obtained by

means of the parcels route.

In my own area of

work, contraband material acquired by marked parcel included

this Kodak camera, it came complete with a supply of film and

photographic

processing chemicals.

|

|

OTHER AIDS TO

ESCAPE

European Money

In addition to

forged papers, money for European countries was an important

item for intending escapers and, in that context; there was an

amusing aspect

to an incident

at Stalag Luft VI. A marked parcel had slipped

through

their system without being spirited out in the intended manner

and, according

to regulations, was being

opened by German security staff in

front

of the designated recipient.

The parcel contained a box

full of European

money! The examiner stared in amazement; recovering, he rushed

to the

door of an office shouting to the security officer 'Come and see

what I've found'. His back was only turned for a matter of

seconds, but that was sufficient for several POWs waiting for

their parcels to grab a handful of money

and to stuff it into their

pockets. The examiner could see that some of the money had

vanished, but said nothing; he probably feared that he would be

on a disciplinary charge for having left the money unattended.

|

|

Compass

Another

item sometimes useful was a compass. Being more enthusiastic at

the time rather than knowledgeable about the feasibility of

escaping, I had made my first compass in the early days at

Stalag VIIIB by magnetizing a razor blade. At that time we had

virtually nothing apart from the clothes

that

we wore. Occasionally though, we received a Red Cross parcel and

amongst

the 'goodies' was a tin of cigarettes. The top of the cigarette

tin was

sealed with a metal foil and, using a pair of nail scissors, the

foil was

cut into a long spiral, producing a sort of wire. That 'wire'

was insulated with paper and wrapped around the razor blade in a

coil. With an improvised fuse, the arrangement was connected

across the electricity

supply in a lamp holder,

there was a flash and a bang and the main electric cutout for

the hut was tripped, my fuse had been ineffective! Nevertheless,

and somewhat to my surprise, the razor blade had been

magnetized, and when suitably

pivoted

made a useable compass. Another

item sometimes useful was a compass. Being more enthusiastic at

the time rather than knowledgeable about the feasibility of

escaping, I had made my first compass in the early days at

Stalag VIIIB by magnetizing a razor blade. At that time we had

virtually nothing apart from the clothes

that

we wore. Occasionally though, we received a Red Cross parcel and

amongst

the 'goodies' was a tin of cigarettes. The top of the cigarette

tin was

sealed with a metal foil and, using a pair of nail scissors, the

foil was

cut into a long spiral, producing a sort of wire. That 'wire'

was insulated with paper and wrapped around the razor blade in a

coil. With an improvised fuse, the arrangement was connected

across the electricity

supply in a lamp holder,

there was a flash and a bang and the main electric cutout for

the hut was tripped, my fuse had been ineffective! Nevertheless,

and somewhat to my surprise, the razor blade had been

magnetized, and when suitably

pivoted

made a useable compass.

|

|

GETTING OUT

OF THE CAMP

Returning to the

topic of escaping, the most obvious problem was to find a way to

get out of the camp.

This photograph shows the outer fence at Stalag Luft I. In

addition to this

double fence, several yards further

in there was a warning wire, to step over that invited a shot

from one of the sentries in the guard towers. Nevertheless, a

number of prisoners did 'have a go' at the wire. Such operations

usually took place at night, but it was a 'dicey business' at

any time, several POWs were shot, or shot at, during such

attempts.

|

|

One of the guard towers or 'Goon boxes' as they were known by

POWs. Note the power and telephone lines, an aspect which

recalls one of the most audacious

individual escape attempts of the war. A POW at Sagan who spoke

fluent German disguised himself as a German camp electrician,

the ruse included

making a dummy electricians test meter. Borrowing a ladder and a

plank

from the camp theatre, the bogus electrician walked up to one of

the guard

towers and explained to the sentry that there was a fault on the

wires and that he had to test them.

Placing the ladder against the

inner fence, the POW climbed up and with the plank bridged the

gap between the inner and outer fences. He then pretended to

check the wiring.

At the far side of the fence he dropped his meter; swearing

profusely in German, he climbed down the outside of the wire,

retrieved the meter and, after examining it, explained to the

guard that it was damaged

and would have to be replaced. He then walked off through the

German part of the camp.

Even the exceptional nerve and initiative of this escaper was

finally unavailing,

he was recaptured at Stettin, a port on the Baltic, after five

days

on the run. However, the man was an inveterate escaper; he

managed to get

out of prison camps on several occasions. On what turned out to

be his last escapade,

which

makes a truly remarkable

story in itself, he finally

disappeared

without a trace.

Having a go at the wire was probably the most dangerous way of

trying to escape,

it took particularly intrepid individuals to take the chance.

There were other, inherently safer options. One reasonably safe

way of getting out of a prisoner-of-war camp was just to walk

out, through the gates! |

|

JUST WALK OUT THROUGH THE GATES

With a forged gate

pass and suitable clothing, persons fluent in German could pose

as a German civilian workman, or even a German guard! Such ruses

were tried on several occasions. |

This

photograph shows parts of a dummy rifle used by a bogus guard at

Stalag Luft III in one of the most daring incidents of that

type. By using a forgery of a gate pass, the bogus guard

successfully marched a whole squad of prisoners out through both

the compound and the main gates of the

camp.

After marching some distance from the camp, the escapers

dispersed into the surrounding countryside. As happened all too

often, they were all eventually recaptured. Although we didn't

achieve anything so spectacular at Stalag Luft I, that tale from

Sagan helps to set the scene for some stories about our own

efforts at forging gate passes. This

photograph shows parts of a dummy rifle used by a bogus guard at

Stalag Luft III in one of the most daring incidents of that

type. By using a forgery of a gate pass, the bogus guard

successfully marched a whole squad of prisoners out through both

the compound and the main gates of the

camp.

After marching some distance from the camp, the escapers

dispersed into the surrounding countryside. As happened all too

often, they were all eventually recaptured. Although we didn't

achieve anything so spectacular at Stalag Luft I, that tale from

Sagan helps to set the scene for some stories about our own

efforts at forging gate passes.

|

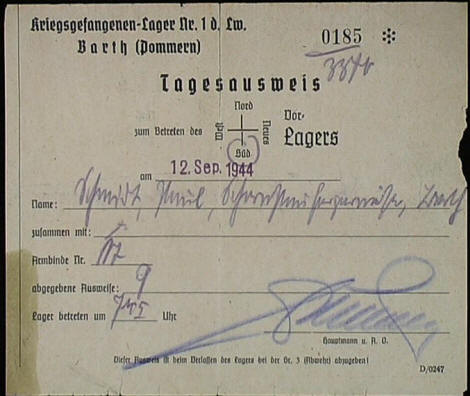

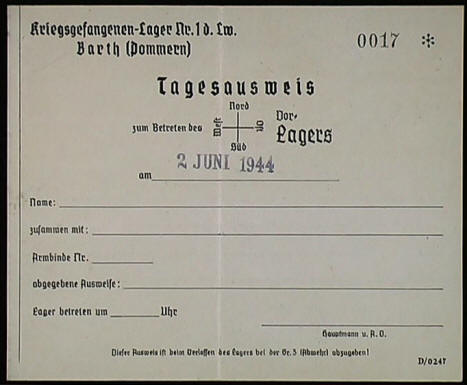

Genuine

Daily Gate Pass Genuine

Daily Gate Pass

This is a genuine daily gate pass that was used at Stalag Luft

I. To increase the security of this gate pass, the abwehr

changed the colour of the pass from day

to day in a random fashion.

|

|

Forged

Daily Gate Pass Forged

Daily Gate Pass

This is a forgery of the daily gate pass, it was copied from a

genuine pass bribed out of one of the camp guards. Although I

drew several of these daily

gate passes, this particular

copy was drawn by an American prisoner-of-war. During the last

year or so of the war American airmen increasingly made up the

majority of the POWs at Stalag Luft I, and we naturally shared

our experience in escape and forgery work with them.

|

|

Camp Guards

A group

of German guards with their officers at Stalag Luft I.

According to the feedback of information that we were able to

obtain from some of the more amenable guards, our forgeries were

so good in general that the gate guards, when they were

questioned by their security officer, were unable to tell the

difference between a genuine gate pass and one of our forgeries

that had fallen into the hands of the abwehr.

|

|

Back of Daily Gate Pass

Shortly

after one of our forgeries

had fallen into the hands of the German security staff, this

intricate pattern was printed on the back of the pass to make

forgery more difficult, if not almost impossible

|

|

Monthly

Gate Pass Monthly

Gate Pass

The problem with a

daily gate pass was that, once it was dated, it was of no

further use if a planned escape attempt had to be postponed for

any

reason to another day.

However, the escape organisation achieved a major success in

acquiring an example

of the genuine monthly gate pass shown here. This was the most

useful gate pass because it was valid for a whole month. Being

so important, it was also correspondingly difficult item to

obtain but, eventually, sufficient pressure was applied to one

of the camp guards to persuade him to loan us his pass.

The guard slipped

the pass through a window of the hut at night when he was on compound

patrol duty. The only method of making a record of a pass at the

time was by hand tracing, and that took several hours.

We only just managed to

return the pass to the guard before his patrol duty ended. The

poor chap must have been on tenterhooks during the intervening

period in case we double-crossed him by keeping his pass. Using

the tracing as a

guide,

a forgery was produced by hand drawing. To my disappointment

after so much hard work, that forgery fell into the hands of the

abwehr at some stage

during the subsequent escape attempt. And it soon became

apparent, through our usual feed-back channels, that I had made

an unforeseen blunder in producing

the forgery.

My forgery would

have been geometrically identical to the original pass from

which it had been traced, but no two original passes would be

identical, with regard to the positions of such individual

additions as date stamps and the signature. The abwehr, just by

recalling all passes issued to the

guards and comparing the

positions of stamps and the signature with those on the forgery,

were able to match the forgery back to the original pass from

which it had been traced. The unfortunate guard who had been

persuaded to loan us his pass eventually received a considerable

prison sentence. Subsequently, we made sure that the positions

of stamps and the signature on a forgery were different from

their position on the original document. |

|

Back

of Monthly Gate Pass Back

of Monthly Gate Pass

The abwehr,

probably

surprised that we could even

obtain, let alone forge such a difficult and strategically

useful item, responded in their usual way by having an intricate

design printed on the back of the pass. I never attempted to

draw this design by hand, looking at it, you can probably

appreciate why.

|

|

|

|

HIDING FORGEIES

Having produced a

forgery, it needed to be securely hidden until the time of use.

This photograph shows one method of hiding documents. It is a

book opened near its centre, the page binding cut through and

the laminations of a cover board largely slit apart. For

illustration, the cover laminations here are being forcibly held

apart. A forgery could be inserted in this gap between the

boards of the cover, the edges of the cover resealed and finally

the back edge of the pages glued together.

|

|

A continual

problem with forging lay in finding paper to make a reasonable

match to the genuine document. With this forgery of another type

of gate pass, it was impossible to find red paper of a shade

near enough to the genuine article. Because of that problem, I

eventually had to draw the pass

on white paper and then

colour it by spraying with water-colour paint using an improvised

sprayer.

|

|

Enlarged

View of Perforations on Gate Pass Enlarged

View of Perforations on Gate Pass

The perforations

for the counterfoil at the bottom of the pass were knocked out

one at a time. To meet the requirements of an escape attempt

that might be arranged at short notice, we tried to keep a stock

of the most useful forgeries. With stock documents, such as this

gate pass, Serial

numbers were left off the forgery to start with: we could then

insert a serial number near to those current at the time the

pass might eventually be used.

|

|

THROUGH THE

GATE

Despite the

technical progress made in forging gate passes, and although

escaping from the camp through the gate was tried on several

occasions, it was, after all, a rather limited option. To have a

reasonable chance of getting through the gates, in addition to a

forgery of the relevant gate pass, it required someone with

considerable fluency in German. Most wouldbe escapers

needed a more widely available option, for instance - a tunnel.

TUNNELS

Tunnels always

seemed to offer the best prospects for getting out of a

prisoner-of-war camp, particularly for the escape of a large

number of people. During the course of the war at Stalag Luft

alone, what now appears to be the surprising figure of about a

hundred tunnels were dug or, more usually,

partly

dug before being discovered by the

abwehr.

|

|

Apart from not requiring fluency in German, tunnels also

promised a reasonably safe means of exit from the camp. A

successful tunnel was what

most people who wanted 'to

have a go' at an escape were waiting for. This cartoon depicts

what you might call 'Lines of communication', to warn of

approaching Germans when a tunnel was being dug.

|

| |

|

Work

on Tunnel 'Harry' Work

on Tunnel 'Harry'

Work at the face

of the most famous tunnel of the war, the 'Great Escape' tunnel

'Harry' at Sagan. This sketch is by F/L Kenyon, DFC, one of

those who succeeded in getting out of the camp during the 'Great

Escape'.

Perhaps one of the

most inconceivable types of tunnel used the technique known as 'Moling'.

It is now difficult to believe that this bizarre method was

feasible at all, let alone actually tried on several occasions.

Definitely not for claustrophobics, the operation'

started by digging a hole

from a vantage point as near to the outer fence as it was

possible to get. The would be escaper was then actually sealed

into the beginning of a tunnel - and this is the almost

unbelievable aspect, with only holes made by something like a

broom handle pushed up through the surface of the ground to

obtain air. The procedure then, was for the tunneller to dig

forward, moving the soil behind him all the time and, as

necessary, pushing the broom handle up through the surface to

obtain air. The soil was light and sandy at both Sagan and

Barth, otherwise the procedure must surely have been

quite

impossible.

|

|

To combat

tunnelling activities, the abwehr deployed microphonic

detectors. Those detectors were buried about four feet deep and

spaced about twenty yards apart around the outer fence. They

were even placed around the exercise compound shown in this

photograph. The detectors proved to be a major problem at Stalag

Luft I, mainly because the water table was so near to the

surface that it was impossible to dig deep enough to get out of

their

range. By contrast, the tunnels for the 'Great Escape' at Sagan

had gone down 28 feet. However, one rather remarkable coup was

pulled off at Stalag Luft I with regard to the tunnel detectors.

From right under the noses of the camp guards, POWs were able to

dig up one of the detectors. We were then able to examine it at

leisure. That quite tricky operation was able to take place due

to the following circumstance.

|

|

As the war

progressed, the Germans needed to enlarge POW camps. That was

usually achieved by adding three sides of a new compound

directly onto the previous perimeter. In one such instance, the

original detectors, which as

a result of the procedure

were then inside the new compound, were not immediately removed

by the abwehr. The escape organisation promptly made

plans

to try to retrieve a detector to see if there might be any way

of combating them. The detectors were inside a new compound for

American prisoners and, with their co-operation, a mock auction

was held to attract a large number of people to screen the

operation from the guards in the overlooking watch towers. A few

POWs went feverishly to work and dug up one of the tunnel

detectors and, as the exceptional crowd was bound to arouse some

suspicion, hurriedly smuggled it away,

just before a guard arrived

on the scene. |

|

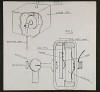

Tunnel

Detector Tunnel

Detector

This drawing of

the tunnel detector was made at the time to provide a technical

record, as we expected intensive searches by the abwehr to

recover their hijacked property. We might also assume that

someone in the abwehr department had his wrist slapped over that

surprising oversight of not removing the detectors prior to

letting prisoners into the compound.

|

|

Entrance

Shaft to 'Harry' Entrance

Shaft to 'Harry'

When tunnels were

being dug, the escape organisation sometimes made a levy on bed

boards to shore-up the roof of the tunnel. This photograph,

taken by the Germans, shows the entrance shaft for the 'Great

Escape' tunnel Harry at Stalag

Luft III, in this instance,

completely lined with bed

boards.

|

|

When tunnels using

bed boards were discovered, the camp administration would

sometimes retaliate,

by making their own levy, to bring

the prisoners' bed boards down to what they thought would be a

very uncomfortable minimum. Most people eventually became

extremely low on bed boards and the escape committee was not

always looked upon too kindly.

Leaving tunnels

for the time being, there were other ways of trying to get out

of a POW camp of course. Hiding amongst the piles of rubbish in

refuse carts was one useful, if smelly idea; that is, until the

Guards routinely prodded the contents of the carts with bayonets

as they went out through the gates of the camp. Not

surprisingly, that method lost its attraction. Once outside the

wire, by whatever means, it was essential that an escaper's

papers were appropriate to the disguise and nationality adopted,

and the escape organisation took every opportunity to acquire

genuine documents that could be copied for use in future escape

attempts. A forgery of one such document, a Polish identity

card, is shown in the next illustration. |

|

Polish

Identity Card Polish

Identity Card

Although

other European nationals brought into the camp were always

escorted by a German guard, it was sometimes possible for a POW

who spoke the necessary language to make contact with the person

being escorted. Contact was made by entertaining or bribing the

guard sufficiently to temper

his enthusiasm for duty. 'Entertainment' could be just an

invitation for the guard to come into a hut and partake of a mug

of real coffee, from Red Cross food parcels, and virtually

unobtainable in wartime Germany. Meanwhile, the guards charge

was being contacted by a POW. There were quite a number of

Polish nationals in the RAF, several eventually becoming POWs:

enabling us to make contact in this instance. This forgery was

copied from a genuine

Polish pass obtained by methods similar to those described.

|

|

DUPLICATING

Inside

of the Polish Pass Inside

of the Polish Pass

The inside of the

Polish identity card, directly hand drawn except

for the stamp,

which was added by our duplicating

process.

|

|

Enlarged

view of stamp on the pass Enlarged

view of stamp on the pass

The duplicated

stamp. We had acquired a simple duplicator quite early on but,

being bulky, it was difficult to hide and was found by the

abwehr during one of their searches. In that type of duplicator

a special ink was

used to draw the image to be

duplicated. Fortunately, the special inks vital to the process

were not found by the abwehr during their search and, after some

experiment, the rather unlikely substance of ordinary table

jelly was used as the ink transfer medium in an improvised

duplicator. The jelly was set to a stiff consistency in a

shallow tray,

and came from special Red Cross

food parcels intended for use in the camp's sick bay.

|

|

Jelly duplicating

was also of service in imitating

duplicated or even typewritten documents. To forge such

documents, the typewriter characters were imitated with a pen.

Ten or even twenty copies could be taken, partly dependent upon

how well the jelly surface stood up to the wear involved. These

two documents are travel permits, they are not very good

examples of that type

of work, but are the only copies that have survived.

|

|

ABWEHR SEARCHES

Snap searches of

the barrack huts by the abwehr were a regular feature of POW

life. Until we gathered experience, several items of contraband

were lost during such searches, including some of my forgeries

that I had hidden in tins buried underneath the huts. It became

a continual game of 'cat and mouse' between the abwehr and the

undercover organisations. Members of the abwehr staff, known by

the POWs as Ferrets, were also continually on the prowl, looking

for any signs of tunnel digging or other illegal activities.

What the abwehr was really after in the artistic line of course,

was evidence of forging.

|

|

Duplicated

Stamps Duplicated

Stamps

The

duplicating process had finally given us an authentic looking

rendition of rubber stamps, and it proved to be quite a step

forward in the forgery business. The stamp was drawn on paper,

using the duplicating ink, then added to a forgery by jelly

transfer. These two stamps were on the back of a pass that

became one of our stock items.

|

|

Pass

for a French POW Pass

for a French POW

This illustration

shows the front of that forgery, and it is the last of our

hand-drawn forgeries to be described. As a number of POWs could

speak some French, this was one of the more-useful items. The

forgery was copied from a pass borrowed from a French soldier

who had been taken as a prisoner-of-war and then forced to work

in Germany. The Frenchman had been escorted into the camp by a

guard and, in the usual way, a prisoner fluent in French was

able to make contact and persuaded the Frenchman to loan us his

pass.

|

|

Enlarged

View of Above Pass Enlarged

View of Above Pass

Much of the

lettering on this pass was very small, and trying to copy it in

the time available was made more difficult by having to break

off work several times during the day when our lookouts deemed

that a German was getting too close to the scene of operations.

Fortunately, a reasonable copy was produced by the time the

original pass had to be returned to its owner.

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHY

Acquiring this

camera by means of the personal parcels route, as described

earlier, was of considerable help in the forgery business. Not

only did it enable a record of an original document to be made

in a relatively short time, it was an essential for producing

acceptable identity photographs for inclusion in forgeries of

identity cards.

|

|

To use the camera to full

advantage, various pieces of ancillary equipment were

constructed. This photograph shows the camera when adapted to

copy documents. The arrangement included an extension bellows

made from brown paper; we could then photograph an original

document at any size we wished up to full size. To vary the

reproduction size, the camera was moved along wooden rails.

There was also a sliding copyboard to facilitate positioning of

the original document; and for illumination, a lamp in a

reflector made from a dried-milk tin. Using this relatively

elaborate set-up, with the ever-present possibility of the

abwehr rushing in was, to say the least, rather an anxious

business.

|

|

Back

of Monthly Gate Pass Back

of Monthly Gate Pass

To indicate how

useful the camera arrangement just described could be, this

illustration shows a print made from a negative that I produced

at Stalag Luft I in 1944, when the escape committee obtained

another example of the monthly gate pass.

Previously, the

only method of making a record of this pattern would have been

to try to copy it by hand tracing.

|

|

Forged

Pass by Photography Forged

Pass by Photography

In one instance

the camera was used to produce a fake pass, saving many

hours of drawing with a

brush. That ausweis, shown here, is also an example of a

document that was just invented to suit a particular escape

attempt.

The wording was

devised by a POW fluent in German. To make up the pass, the

individual words were cut from a German magazine and pasted-up

to give the required format. The paste-up was then photographed

with the camera arrangement just described. The authorising

stamps were added to the final photographic print by jelly

transfer.

|

|

HIDING

PHOTOGRAPHIC

EQUIPMENT

Camera Set-up

This photographic

set-up was made so that it could be easily dismantled. Many of

the individual pieces then gave no indication of their ultimate

purpose and could be left in view with little danger of being

confiscated. That situation was aided by the fact that many POWs

made weird and wonderful gadgets from any odd pieces of wood or

metal that they could find.

|

|

Camera in brick

Across the middle

of the barrack hut there was a brick fire-wall, a brick was

removed from the fire wall in the loft area where it was quite

dark and a wooden box was constructed to the same size as the

brick; that box was just large enough to take the folded camera.

The box was fitted back into the fire wall and a slice of brick

was fixed to each end of the box to match the rest of the wall.

One of the slices of brick was removable, being fixed

with-counter-sunk

screws. The top of the screw holes were then filled with a

paste, made of chewed, German 'black' bread, that made a

reasonably

good match to the texture of the

brickwork, and it could easily be removed and replaced whenever

the camera was to be used. That hiding place was almost

impossible for the abwehr to discover. Nevertheless, had we been

caught in a snap search raid while the camera set-up was

actually in use, we would probably have been in considerable

trouble. As it was, the camera served us well until the end of

the war.

|

|

RETURN TO 'Z'

Leaving

photographic work, we come to our last major area of undercover

activity. The subject of the next illustration, apart from

providing a lead-in to the story, has quite a dramatic relevance

a little later on.

The 7th of June 1944 and one of the few occasions when a German

newspaper was eagerly received by POWs. The Deutsche Allgemeine

Zeitung announcing the Allied invasion of Europe. Actually, we

sometimes knew more about what was going on than the German

public, and that remark heralds a return to the 'Z' section, and

the story of the Stalag Luft I radio. The 7th of June 1944 and one of the few occasions when a German

newspaper was eagerly received by POWs. The Deutsche Allgemeine

Zeitung announcing the Allied invasion of Europe. Actually, we

sometimes knew more about what was going on than the German

public, and that remark heralds a return to the 'Z' section, and

the story of the Stalag Luft I radio.

|

|

THE SECRET RADIO

The radio was

constructed by one of my room-mates, W/O Leslie Hurrell.

Although the major components would have been acquired in the

usual way by

bribing or blackmailing guards,

building a working radio under the conditions that appertained

in a POW camp would have required considerable improvisation and

ingenuity. Finding our radio ultimately became one of

the prime

objectives of abwehr searches. As the radio was relatively

bulky, hiding it securely whilst still being able to use it

easily, had presented some major problems. The eventual solution

is described with reference to the following few photographs.

|

|

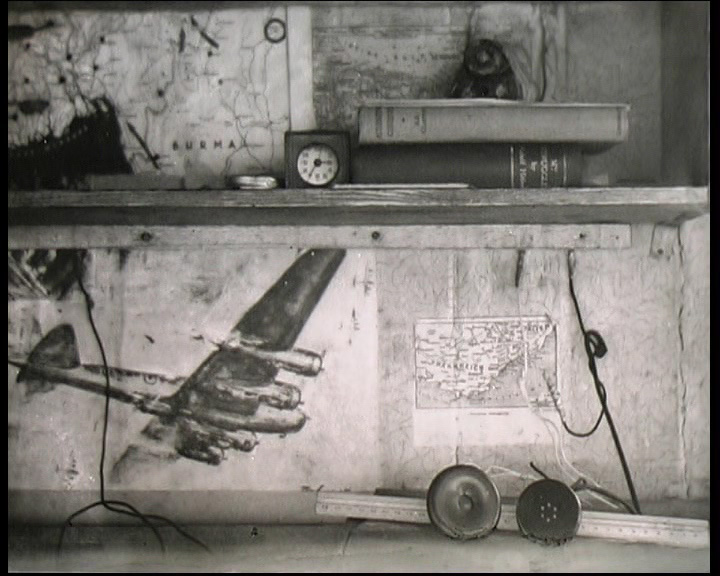

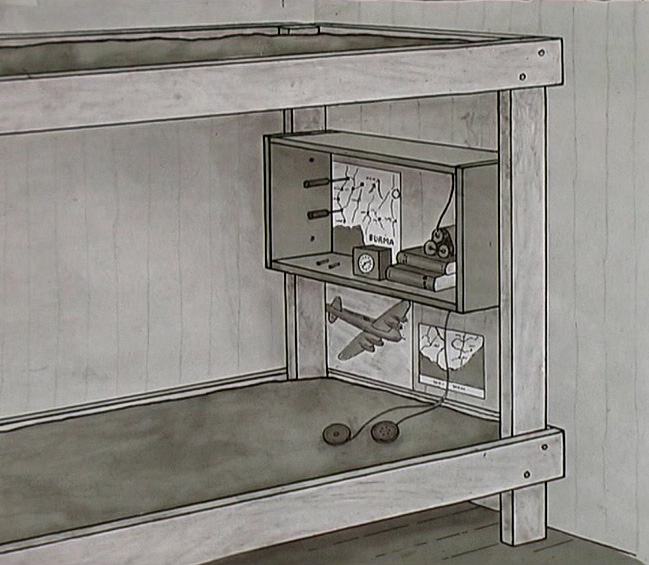

The

Radio The

Radio

This illustration

shows a board pried from the inner wall of the hut with the

radio fixed to the back of the board. As can be seen from the

photograph the radio was a two valve job.

The wallboard with the radio on the

back has been put in place, pictures and maps from German

newspapers have been pasted over the joins of the wallboards, my

bunk-bed has been pushed back into position against the wall and

a book-shelf fixed over the critical position. To make contact

with the radio, wires were pushed through holes in the wall

boards. Those holes were positioned as inconspicuously as

possible and normally filled with plugs made to match the rest

of the wall. This photograph shows the radio ready to be used.

The batteries to operate the radio are on top of the books on

the bookshelf, the earphones are resting on the blanket of my

bunk-bed.

|

|

To

tune-in the radio stations it was necessary to adjust the two

variable capacitors in the radio by means of screwdrivers also

pushed through holes in the wallboard. Unavoidably, those holes

were in a more-exposed position and, to camouflage them, the

holes were bored through one of the newspaper maps that had been

suitably positioned on the wall. To

tune-in the radio stations it was necessary to adjust the two

variable capacitors in the radio by means of screwdrivers also

pushed through holes in the wallboard. Unavoidably, those holes

were in a more-exposed position and, to camouflage them, the

holes were bored through one of the newspaper maps that had been

suitably positioned on the wall.

|

|

Plugs

for those holes were then disguised to look like the towns that

were genuinely part of the map. Those plugs could be removed

with a pin when the radio

was to be used. For security, we chose a map of a remote

geographical area. On the left of this map of Burma,

screwdrivers can be seen inserted through our two fictitious

town. Even the most observant guards were unlikely to have

noticed anything strange about our alteration to the topography

of such a remote and little-known area. Plugs

for those holes were then disguised to look like the towns that

were genuinely part of the map. Those plugs could be removed

with a pin when the radio

was to be used. For security, we chose a map of a remote

geographical area. On the left of this map of Burma,

screwdrivers can be seen inserted through our two fictitious

town. Even the most observant guards were unlikely to have

noticed anything strange about our alteration to the topography

of such a remote and little-known area.

|

|

The location of

the hidden radio in relation to the bunk bed. Although the

system worked well, we didn't get away with it quite that

easily. The abwehr knew or suspected that we had a radio, and on

the night of the 6th June 1944 our luck finally ran out.

|

|

The 6th of June

was the day of the Allied invasion of Europe, and the abwehr had

no doubt assumed, correctly of course, that the

prisoners-of-war would be avid for news of that long-awaited

operation and must have thought that it would be an ideal time

to pounce and perhaps catch the radio operators in action. And

indeed, while the BBC midnight news, 1 am our time, was being

taken down from the radio, we were caught in a snap search raid!

Obviously timed to coincide with the most likely BBC news

broadcast, the abwehr mounted their largest night-time raid.

Choosing the critical moment,

twenty or so abwehr men rushed into the hut, several of them

entering each room almost simultaneously. Although we had the

usual duty lookout, there was only a few seconds warning.

Frantically, the

wires were removed and plugs reinserted in the wall. But there

was no time

to put the batteries and earphones into their normal secure

hiding places, they were just pushed under a bed, Virtually as

the guards burst into

the room. As it was my bed, it was my turn to be on tenterhooks.

In fact,

I found the strain so great as the abwehr started their search

that I walked out into the corridor, waiting for the shout of

triumph as the seemingly inevitable discovery was made.

To my surprise, and utter

relief, nothing happened! Apparently, my bed was the only one in

the room that the guards had not looked under! I can only assume

that, in the general confusion, each of the guards must have

thought that one of his partners had checked that particular

bed. After that almost unbelievable escape from disaster, the

radio survived safely until the end of the war, undetected in

many future searches. |

|

Under more-normal conditions, the BBC midnight news was taken

down on most

nights by Lieutenant Lou Trouve, a

POW from the American Army Airforce who was proficient in

shorthand, The notes were transcribed the next morning and then

read out in each hut. The written transcript was then destroyed.

This photograph of Lou Trouve was taken in 1946 after he had

returned to his profession as a journalist in New York.

Lou Trouve |

|

Lou Trouve also

played a part in another aspect of the undercover radio work at

Stalag Luft I. The radio program 'The Voice of America' often

included coded messages for American prisoners-of-war, some of

whom are seen here at Stalag Luft I. Again, those programs had

to be monitored in the middle of the night and taken down

verbatim in shorthand. The shorthand notes were transcribed the

next day to see if there were any messages relevant to Stalag

Luft I.

As the radio was hidden in the

wall at the foot of my bunk-bed, receiving the 'The Voice of

America' program at 2 am in the morning in addition to the BBC

news at 1 am, meant that I lost quite a lot of sleep during the

last year

or so of the war.

|

|

Transceiver Transceiver

To bring the radio

story to a close, during the latter part of the war, and again

thanks to the personal parcels route for contraband, an American

combined radio transmitter and receiver was safely obtained at

Stalag Luft I. To smuggle an item of that size and weight

through the German security was quite a feat. Although the

radio was not necessary for our already established news

service, it did give the American contingent the opportunity to

set up a radio new service of their own. The transceiver also

offered a possible emergency link to the relieving forces in the

very uncertain and probably dangerous weeks expected at the

end of the war.

|

| The

radio operations are the last of the undercover activities to be

described in this record of secret work at Stalag Luft I, and to

round-off

the overall picture, part 3

continues the narrative with a few aspects of the camp's

eventual liberation, ending with an epilogue of half a century

later. |

|